Salmonflies

Pteronarcys californica

The giant Salmonflies of the Western mountains are legendary for their proclivity to elicit consistent dry-fly action and ferocious strikes.

Featured on the forum

Nymphs of this species were fairly common in late-winter kick net samples from the upper Yakima River. Although I could not find a key to species of Zapada nymphs, a revision of the Nemouridae family by Baumann (1975) includes the following helpful sentence: "2 cervical gills on each side of midline, 1 arising inside and 1 outside of lateral cervical sclerites, usually single and elongate, sometimes constricted but with 3 or 4 branches arising beyond gill base in Zapada cinctipes." This specimen clearly has the branches and is within the range of that species.

Troutnut is a project started in 2003 by salmonid ecologist Jason "Troutnut" Neuswanger to help anglers and

fly tyers unabashedly embrace the entomological side of the sport. Learn more about Troutnut or

support the project for an enhanced experience here.

Insect Order Ephemeroptera (Mayflies)

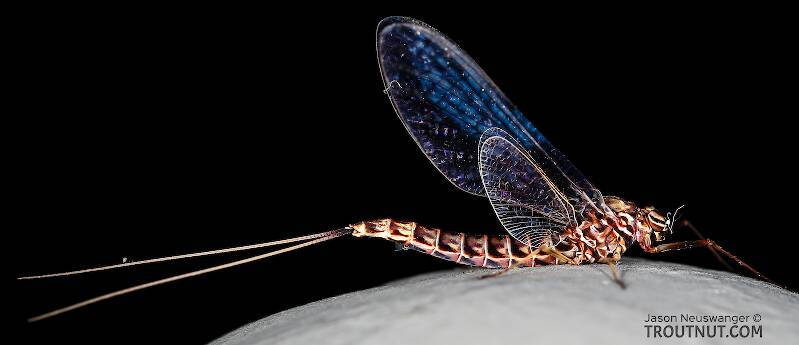

Mayflies live more than 99% of their lives as nymphs on the river or lake bottom, filling many crucial roles in freshwater ecosystems as they feed and grow. They eventually emerge from the water as winged sub-adults called "subimagos" by scientists and "duns" by anglers. Duns evolved to be good at escaping the water, with a hydrophobic surface and hardy build, but they are clumsy fliers. Within a day or two they molt one last time into "imagos" or "spinners," the mature adults, a transformation captured in this photo series of a dun molting into a spinner. They have longer legs and tails, and sleeker, more lightweight bodies, giving them the airborne speed, agility, and long grasp they need for their midair mating rituals. They are usually darker than the duns and have shinier, more transparent wings. They die within minutes or hours after mating.

Hatching behavior

The importance of mayflies comes largely from their emergence and mating behavior. While many organisms assure the survival of their species using individualistic tools like stealth, speed, venom, or parental care, mayflies are famous instead for their "strength in numbers" approach. They coordinate their emergence and mating times (both time of year and time of day) so that they leave their safe habitats and emerge together in large numbers in a very short period of time. This can trigger feeding frenzies in every nearby insect-eater, from trout to birds to dragonflies, but there are simply so many mayflies at once that many luck out and survive to reproduce. These trout feeding frenzies are the stuff of legend among fly anglers, and they also pose one of our greatest challenges, because trout feeding feverishly on a thick hatch are often unwilling to strike any fly that doesn't properly imitate the mayfly of the hour.The duns of each species typically emerge during an hour or two each day for a couple of weeks in the spring or summer, though there are some important fall hatching species. Some species follow more sporadic emergence strategies, and many of these combine to create a sort of "background noise" of miscellaneous mayfly activity on many trout streams throughout much of the summer. This mixed bag of mayflies provides good opportunities for anglers to catch rising trout that aren't too picky.

Mayfly nymphs emerge into duns in several different ways. Most often, the nymph swims to the water's surface and splits open its exoskeleton above the thorax. The dun wriggles out onto the surface, where its wings fill with fluid hydraulically and allow it to take flight. (In contrast to the common myth of mayflies needing time to "dry their wings," this process is more like inflating a raft.) Different species may be quick or slow at each stage of this process. Some take a long time to escape their nymphal shuck, making flies that imitate these "emergers" especially effective. Some species very quickly take flight when they hit the surface, while others ride the surface for some minutes like little sailboats, a prime target for hungry trout and a welcome sight for the dry fly angler. Cool or windy weather may prolong these struggles and increase the availability of mayflies to trout.

Many important species follow completely different emergence patterns. In some, full winged duns emerge on the bottom of the stream and float to the surface. Others swim to shore and crawl out on land before emerging. Learning to identify mayflies and associate them with the right behaviors gives an angler an advantage: the ability to make a good guess about which style and stage of emergence to imitate, simply from seeing and recognizing some duns or mature nymphs.

Spinner behavior

Once mayflies have molted into spinners (imagos), they usually gather in swarms to mate, usually over riffles. When they're done they fall dead, or spent, on the water in an event anglers call a spinner fall. Spinner falls are usually better coordinated than emergences, because spinners gather in swarms for mating. This means some species with sporadic, unnoticed dun emergences become far more concentrated and important to anglers as spinners.Spinner falls are also usually more predictable than emergences, because so many of them (although not all) take place at dusk, and they are preceded by visible aerial spinner swarms, which may start hours earlier at treetop level and descend gradually toward the water as night falls. Dusk spinner falls often mark the angler's best chance to see a good rise of trout each day. However, like most things in nature, mayfly spinners aren't as predictable as we'd like. Sometimes clouds of thousands of spinners will gather over a riffle in the evening and fly back into the woods as quickly as they came, never falling spent. When that happens, anglers must swallow their disappointment and look for them to finish the job in the morning.

Mayfly females face the extra duty of laying their eggs after mating. Many species release their eggs as they fall spent on the water near the males after mating. Some land on the water, release a few eggs and take off again. Others fly low over the water and dip the tips of their abdomens below the surface for just a moment to release eggs. Still others drop their eggs from high in the air. In one very common genus, Baetis, the females land near shore and crawl underwater to lay their eggs in neat little rows on rocks and logs.

Nymph biology

Anglers recognize four categories of mayfly nymphs: swimming, burrowing, clinging, and crawling:

- Some streamlined swimmers move like little bullets, faster then fish of the same size, and they swim upstream against strong current without a problem. Others inhabit slow water and use their speed to dart between leaves in the weed beds.

- Clingers of the family Heptageniidae are typically flat nymphs with strong legs and claws for holding on to rocks. Some have evolved further adaptations for clinging in fast water; for example, the genus Rhithrogena has gills resembling suction cups. There is great variation among the clingers and some species have adapted to slow water.

- Crawlers come in the most varied forms; they are a catch-all group for "average" families that usually excel at neither swimming nor clinging. The Hendricksons and Sulphurs of the Ephemerella genus are typical crawlers. There are tiny crawlers like Tricorythodes, and there are oddballs like Baetisca. The crawlers in Leptophlebiidae are quite good at swimming, and those in Drunella (especially Drunella doddsii) are quite good at clinging.

- The distinctive burrowers of Ephemeridae (and the less important Polymitarcyidae) are pale nocturnal creatures which use tusks to carve U-shaped burrows into the river bottom, where they live most of the time. Their long yellow bodies and feathery gray gills make them unmistakable. Their hatches are some of the angler's favorites, especially the giant Hexagenia limbata flies of the Midwest and West or the Eastern Green Drakes, Ephemera guttulata.

Entomologists have a similar system, but even their line between categories is a blurry one. Some burrowers swim well, some crawlers cling well, and some families like Leptophlebiidae and Potamanthidae straddle the boundary between categories.

If you fish a fertile stream, watch the bottom ahead of you as you walk. Sometimes, especially in April and May, you'll see lots of mayfly nymphs in front of you swimming out of your way or scurrying to the undersides of rocks. You don't need to be down on all fours with a magnifying glass to see mayfly life underwater.

Identification

To further identify a specimen of Ephemeroptera to the family level, use the Key to Families of Mayfly Nymphs or Key to Families of Mayfly Duns and Spinners.

Specimens of Mayflies:

10 Male Duns

9 Female Duns

10 Male Spinners

9 Female Spinners

10 Nymphs

18 Streamside Pictures of Mayflies:

18 Underwater Pictures of Mayflies:

Discussions of Ephemeroptera

Possible ID

1 replies

Posted by Sreyadig on Apr 11, 2021 in the species Apobaetis futilis

Last reply on Apr 11, 2021 by Taxon

In searching for nymphs in my small stream in northern Maryland, 500 yards from the PA line, I came across a 2 tailed mayfly that was not a of the Epeorus genus.

It was in a fast riffle section along with Epeorus nymphs. This was about 3/8” in overall length including tails. Darker straw coloration with dark brownish black wing cases that were pronounced in color and shape. Biggest factor was the tails. Median caudal filament was truncated, very small compared to the outer pair. Not even sure if tail/ caudal filament should be used to describe. In my books the closest thing is the Pseudocloeon futile. Which is an old taxonomic name I’m finding out.

This find seems rare in my area and experience. Hopefully I can get a photo...

It was in a fast riffle section along with Epeorus nymphs. This was about 3/8” in overall length including tails. Darker straw coloration with dark brownish black wing cases that were pronounced in color and shape. Biggest factor was the tails. Median caudal filament was truncated, very small compared to the outer pair. Not even sure if tail/ caudal filament should be used to describe. In my books the closest thing is the Pseudocloeon futile. Which is an old taxonomic name I’m finding out.

This find seems rare in my area and experience. Hopefully I can get a photo...

Yea...

Posted by Imaxfli on Oct 23, 2020 in the species Ephoron leukon

Last reply on Oct 23, 2020 by Imaxfli

Me too looking for photos or better yet, video of matching. These things seem to pop outa the water like no other ......

Trico emergers

6 replies

Posted by Bwoklink on Jul 14, 2018 in the genus Tricorythodes

Last reply on Sep 11, 2020 by Martinlf

Anyone have experience fishing Trico emergers patterns? I've had experience fishing the winged and spinner stage, but haven't heard of anyone fishing emergers during the early morning female hatch. Anyone used emerger patterns and if so would you might sharing which ones you have found effective?

PMD Spinner - Egg sack color?

20 replies

Posted by Wbranch on Jan 26, 2010 in the species Ephemerella excrucians

Last reply on Aug 18, 2020 by Troutnut

Do any of you entomologist types know the true color of the PMD spinner? Dorothea or excrucians. Where I fish in MT there are huge spinner falls, many spents are on the water in the morning and others fall again at various periods during the day. I'd like to tie some with egg sacks as I saw many in July but forgot what color they were. Thanks.

Trico Tips

50 replies

Posted by Martinlf on Jul 21, 2007 in the genus Tricorythodes

Last reply on Jul 31, 2020 by Martinlf

I'll start with a fly patterns, follow with a bit of what I think I know about Tricos (Entomologists, please offer corrections if needed), and close with a few questions.

I love designing different patterns for Tricos, partly to keep myself entertained, and partly to show the fish something new from time to time. Jason's photos and the opinions of some fussy fish have led me to tie an extra large thorax recently on all my Tricos. My old standby is a parachute tied reverse, with a high vis post over the bend of the hook, and grizzly hackle, with no tails. It's modeled on Al's Trico, which could be found on the Little Lehigh Flyshop website until Rod closed the shop. An internet search may provide images now. It's very visible and fish generally approve. My newest fly is a take off from one of Gonzo's (Lloyd Gonzales) patterns in his book Fly-fishing Pressured Water, and it also shows the influence of Al's Trico. Gonzo ties an upside down Trico on a wide gap hook using synthetic material for the wing. I tie this fly also, and it certainly does catch fish, but I recently tied a version with grizzly hackle, making an oversize thorax and palmering hackle over the thorax to create a full wing. I then clipped hackle from the top of the fly (which becomes the bottom, as this is an upside down fly) so that the fly would sit flat, upside down, on my tying table. A drop of Locktite brush-on super glue on the bare recently clipped thorax after darkening the hackle stem with black marker and the fly was done. (By the way, I put tails on this one to balance it [P.S. Later correction: this pattern doesn't need the tails. I've caught plenty fish now on a tailless version] .) It caught several fish the first time I tried it on a heavily fished stream.

I believe for some, if not most species of Tricos, males hatch at night, females in the morning, and that the spinners fall when the air temperature hits the upper 60's. This generally means that as the season goes on, spinners hit the water later and later. Sometimes by 7:00 am (or earlier) in the early summer, by 10:00 (or later) in the fall.

It's been unseasonably cool in the Northeast the past couple of days, and I would have gone out this morning but for taking my daughter to a midnight showing of The Order of the Phoenix (I just couldn't get up) but I'm wondering if the spinner fall happens later than normal on cool mid-summer mornings like today's. I hope to find out Monday, but am curious if anyone has experiences to share. Also, does anyone have an effective Trico pattern to share? I'm always looking for ideas.

I love designing different patterns for Tricos, partly to keep myself entertained, and partly to show the fish something new from time to time. Jason's photos and the opinions of some fussy fish have led me to tie an extra large thorax recently on all my Tricos. My old standby is a parachute tied reverse, with a high vis post over the bend of the hook, and grizzly hackle, with no tails. It's modeled on Al's Trico, which could be found on the Little Lehigh Flyshop website until Rod closed the shop. An internet search may provide images now. It's very visible and fish generally approve. My newest fly is a take off from one of Gonzo's (Lloyd Gonzales) patterns in his book Fly-fishing Pressured Water, and it also shows the influence of Al's Trico. Gonzo ties an upside down Trico on a wide gap hook using synthetic material for the wing. I tie this fly also, and it certainly does catch fish, but I recently tied a version with grizzly hackle, making an oversize thorax and palmering hackle over the thorax to create a full wing. I then clipped hackle from the top of the fly (which becomes the bottom, as this is an upside down fly) so that the fly would sit flat, upside down, on my tying table. A drop of Locktite brush-on super glue on the bare recently clipped thorax after darkening the hackle stem with black marker and the fly was done. (By the way, I put tails on this one to balance it [P.S. Later correction: this pattern doesn't need the tails. I've caught plenty fish now on a tailless version] .) It caught several fish the first time I tried it on a heavily fished stream.

I believe for some, if not most species of Tricos, males hatch at night, females in the morning, and that the spinners fall when the air temperature hits the upper 60's. This generally means that as the season goes on, spinners hit the water later and later. Sometimes by 7:00 am (or earlier) in the early summer, by 10:00 (or later) in the fall.

It's been unseasonably cool in the Northeast the past couple of days, and I would have gone out this morning but for taking my daughter to a midnight showing of The Order of the Phoenix (I just couldn't get up) but I'm wondering if the spinner fall happens later than normal on cool mid-summer mornings like today's. I hope to find out Monday, but am curious if anyone has experiences to share. Also, does anyone have an effective Trico pattern to share? I'm always looking for ideas.

Start a Discussion of Ephemeroptera

References

- Baumann, Richard W. 1975. Revision of the Stonefly Family Nemouridae (plecoptera) : a Study Of The World Fauna At The Generic Level. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology undef(211): 1-74.

- Jacobus, L. M., Wiersema, N.A., and Webb, J.M. 2014. Identification of Far Northern and Western North American Mayfly Larvae (Insecta: Ephemeroptera), North of Mexico; Version 2. Joint Aquatic Science meeting, Portland, OR. Unpublished workshop manual. 1-176.

- Merritt R.W., Cummins, K.W., and Berg, M.B. 2019. An Introduction to the Aquatic Insects of North America (Fifth Edition). Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

Insect Order Ephemeroptera (Mayflies)

Taxonomy

Family in Ephemeroptera

AmeletidaeBrown Duns

25

123

Ametropodidae

0

0

Arthropleidae

0

0

BaetidaeBlue-Winged Olives

115

642

BaetiscidaeArmored Mayflies

25

140

CaenidaeAngler's Curses

11

30

EphemerellidaeHendricksons, Sulphurs, PMDs, BWOs

282

1467

EphemeridaeHexes and Big Drakes

57

315

HeptageniidaeMarch Browns, Cahills, Quill Gordons

241

1364

IsonychiidaeSlate Drakes

21

117

LeptohyphidaeTricos

13

66

LeptophlebiidaeBlue Quills and Mahogany Duns

66

335

MetretopodidaePseudo-Gray Drakes

11

39

Neoephemeridae

1

7

Palingeniidae

0

0

PolymitarcyidaeWhite Flies

0

1

PotamanthidaeGolden Drakes

0

0

Pseudironidae

0

0

SiphlonuridaeGray Drakes

24

122

Family in Ephemeroptera: Ameletidae, Ametropodidae, Arthropleidae, Baetidae, Baetiscidae, Caenidae, Ephemerellidae, Ephemeridae, Heptageniidae, Isonychiidae, Leptohyphidae, Leptophlebiidae, Metretopodidae, Neoephemeridae, Palingeniidae, Polymitarcyidae, Potamanthidae, Pseudironidae, Siphlonuridae

4 families (Acanthametropodidae, Behningiidae, Euthyplociidae, and Oligoneuriidae) aren't included.

Identification Keys

Common Name

Resources

Mayfly Central maintains a useful, up-to-date species list of North American mayflies.

Ephemeroptera Galactica maintains an incredible archive of scientific publications with full-text PDFs about mayflies.

Ephemeroptera Galactica maintains an incredible archive of scientific publications with full-text PDFs about mayflies.