Salmonflies

Pteronarcys californica

The giant Salmonflies of the Western mountains are legendary for their proclivity to elicit consistent dry-fly action and ferocious strikes.

Featured on the forum

Troutnut is a project started in 2003 by salmonid ecologist Jason "Troutnut" Neuswanger to help anglers and

fly tyers unabashedly embrace the entomological side of the sport. Learn more about Troutnut or

support the project for an enhanced experience here.

Mayfly Family Heptageniidae (March Browns, Cahills, Quill Gordons)

Known as the "clinger" mayflies to anglers, a few species of this family can be extremely prolific, with a lot more that aren't. These lesser species account for many of the curious mayflies you find that never seem to associate with a major hatch, let alone a fishable one. Not all heptageniid species are so scarce though; there are superhatches too.

Heptageniids can be broken into "groups" of similar genera (based on angling concerns) to help keep track of them. Although many of them are closely related, they are not officially divided in this way by entomologists. Here are the groups:

The genus Stenonema, who's Latin name was one of the first etched in the minds of anglers, was for a while largely reclassified into Maccaffertium but has since been reinstated. It includes the March Brown (S. vicarium) and Gray Fox (previously S. fuscum) superhatches.

The Stenonema species are for all practical purposes limited to the East and Midwest.

While Heptagenia has held on to several species, many of its fishable hatches have been moved to the genera Leucrocuta, Nixe, and Ecdyonurus. Some species of Nixe were subsequently moved to Afghanurus. There are many former Heptagenia species across the continent, but few are important to anglers. Of those, more are in the West than in the East.

The closely related genera Epeorus and Ironodes are among the only mayflies to have just two tails as nymphs. Good populations can be found in the West, but it's in the East where the mayfly named after the man that brought the dry fly to America can be found, the superhatch Epeorus pleuralis or Quill Gordon.

The genus Rhithrogena can be identified by the gills of its nymphs. They extend underneath the abdomen in the front and the back. They are very important for early season anglers in the West, but not very often in the East. For western anglers, it's duns are the blotchy winged equivalent of the East's March Brown (Maccaffertium vicarium). Ironically, it is only the Western March Brown that is in the same genus as the English species for which the common name originated.

The genus Cinygmula is easily distinguished by the nymph's enlarged palpi (mouth parts) that stick out from both sides of their heads like little blunt horns. They rarely produce fishable hatches, and none are of much significance except for a few species, mostly in certain locales of the West.

Heptageniids can be broken into "groups" of similar genera (based on angling concerns) to help keep track of them. Although many of them are closely related, they are not officially divided in this way by entomologists. Here are the groups:

Stenonema (blotchy wings)

The genus Stenonema, who's Latin name was one of the first etched in the minds of anglers, was for a while largely reclassified into Maccaffertium but has since been reinstated. It includes the March Brown (S. vicarium) and Gray Fox (previously S. fuscum) superhatches.

The Stenonema species are for all practical purposes limited to the East and Midwest.

Former Heptagenia (plain wings)

While Heptagenia has held on to several species, many of its fishable hatches have been moved to the genera Leucrocuta, Nixe, and Ecdyonurus. Some species of Nixe were subsequently moved to Afghanurus. There are many former Heptagenia species across the continent, but few are important to anglers. Of those, more are in the West than in the East.

Epeorus (two-tailed Nymphs, plain wings)

The closely related genera Epeorus and Ironodes are among the only mayflies to have just two tails as nymphs. Good populations can be found in the West, but it's in the East where the mayfly named after the man that brought the dry fly to America can be found, the superhatch Epeorus pleuralis or Quill Gordon.

Rhithrogena (suction cup gills)

The genus Rhithrogena can be identified by the gills of its nymphs. They extend underneath the abdomen in the front and the back. They are very important for early season anglers in the West, but not very often in the East. For western anglers, it's duns are the blotchy winged equivalent of the East's March Brown (Maccaffertium vicarium). Ironically, it is only the Western March Brown that is in the same genus as the English species for which the common name originated.

Cinygmula (horn heads)

The genus Cinygmula is easily distinguished by the nymph's enlarged palpi (mouth parts) that stick out from both sides of their heads like little blunt horns. They rarely produce fishable hatches, and none are of much significance except for a few species, mostly in certain locales of the West.

Family Range

Hatching behavior

Many heptageniid mayflies emerge from their nymphal shucks on the stream bottom or during their rise to the surface. Others hatch in the surface film. Others still migrate to the shallow margins and use any of the three ways. All of this may depend on habitat and current conditions as much as differences between species. Read about the species you need to match for more details, but there is no substitute for astute observation streamside.

Nymph biology

The Heptageniidae family contains the angler's "clinger" type mayfly nymphs commonly referred to as "Flat Heads" by entomologists. They sport flattened profiles, blunted broad heads, and stout legs suitable for life in fast water. Their flattened tear drop shape is a "miracle" of nature's hydrodynamic engineering employing the same principles used by Formula One race cars to hug the road and reduce wind resistance.Identification

To determine whether a specimen of Ephemeroptera belongs to Heptageniidae, use the Key to Families of Mayfly Nymphs or Key to Families of Mayfly Duns and Spinners.

Specimens of the Mayfly Family Heptageniidae

15 Male Duns

15 Female Duns

15 Male Spinners

15 Female Spinners

15 Nymphs

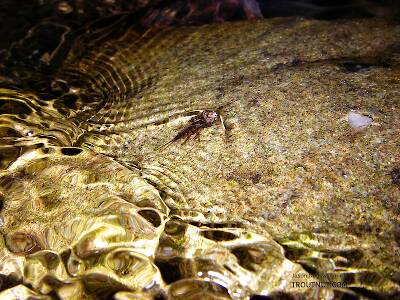

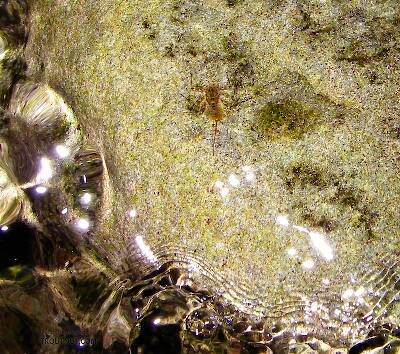

10 Streamside Pictures of Heptageniidae Mayflies:

11 Underwater Pictures of Heptageniidae Mayflies:

Discussions of Heptageniidae

Clinger nymphs are shaped that way to hang in really fast currents. Really?

14 replies

Posted by Entoman on Feb 23, 2013 in the genus Rhithrogena

Last reply on Jun 14, 2017 by Steamntrout

It is commonly held that clingers are flattened to make their lives better adapted to faster water. Their teardrop shape is certainly a classic symbol of aero and hydrodynamic perfection, so there must be some connection, right? It seems to me that such ideas show a complete misunderstanding of the hydraulic reality in which they live. Current is negligable even in the fastest a few mm. from the surface of solid objects. In fact, it is actually quite calm. I've observed baetids clinging by their tippy toes to the tops of rocks in fast riffles with no apparent effort, often next to clinger species that look like they're hanging on for dear life. What if clinger nymphs are flattened not to hold their place in fast currents but rather to facilitate movement in their ecological niche of the cramped spaces under and between cobble or crevices in other substrate types?

It is also thought that the gills of some species form ''suction'' to hold them in place. Since suction is a phenomena of vacuum creation in the atmosphere, how are these nymphs accomplishing this underwater? Is it their ultra delicate gills that hold them in place or a firm claw grip? The horizontal sprawl of the legs masks this as the gills stay in place until the legs brake free. Exposed to the air, the gills seem to laminate against the rock, just as crepe paper would if first held underwater before a rock was lifted out into the air from underneath it. However, underwater their gills behave like the crepe, flowing freely. They are performing their function as gills not suction cups. I find it hard to believe they evolved the way some think merely so they can make it more difficult for humans to pluck them from rocks in the atmosphere. How is it these mighty structures that defy our attempts to pry them from the rocks curiously fall off so easily when prodded for inspection a few seconds later in a tray or jostled in a container on the way home?

Even many scientific papers have encouraged these dubious beliefs so it's not just angler myth... And they go unchallenged... Thoughts?

It is also thought that the gills of some species form ''suction'' to hold them in place. Since suction is a phenomena of vacuum creation in the atmosphere, how are these nymphs accomplishing this underwater? Is it their ultra delicate gills that hold them in place or a firm claw grip? The horizontal sprawl of the legs masks this as the gills stay in place until the legs brake free. Exposed to the air, the gills seem to laminate against the rock, just as crepe paper would if first held underwater before a rock was lifted out into the air from underneath it. However, underwater their gills behave like the crepe, flowing freely. They are performing their function as gills not suction cups. I find it hard to believe they evolved the way some think merely so they can make it more difficult for humans to pluck them from rocks in the atmosphere. How is it these mighty structures that defy our attempts to pry them from the rocks curiously fall off so easily when prodded for inspection a few seconds later in a tray or jostled in a container on the way home?

Even many scientific papers have encouraged these dubious beliefs so it's not just angler myth... And they go unchallenged... Thoughts?

M. ithaca in M. mediopunctatum section?

3 replies

Posted by GONZO on Sep 1, 2012 in the species Stenonema mediopunctatum

Last reply on Sep 4, 2012 by Entoman

Hi Jason,

In this section, the Midwestern nymphs (#573 & #574) with the dark irregular ventral bars across the anterior portion of the sternites look like Maccaffertium mediopunctatum arwini (the Midwestern ssp.), but the two Eastern duns (#733 & #765) and the associated shuck (of #765) and nymph (#764) look more like Maccaffertium ithaca to me.

Three Maccaffertium species can have very similar ventral markings in the nymph—dark, sinuate, chevron-shaped bars on many of the sternites and dark lateral marks (sometimes connected to form an inverted U-shaped mark) on segment 9. The Eastern mediopunctatum subspecies, M. m. mediopunctatum, has these markings, as does M. ithaca. Similar markings also appear as a less-common variant marking of M. modestum (or the M. modestum species complex). However, these species differ in the length and location of posterolateral projections, leg markings, the appearance of the subs and adults, and size.

Although interpretation of posterolateral projections can be tricky, those projections should help to separate the nymph (and husk) from mediopunctatum. On mediopunctatum, projections are usually on segments 3-9, 4-9, or 5-9, and those on 8 and 9 are fairly long. On ithaca, projections are usually on segments 6-9 or 7-9, and those on 8 and 9 are somewhat shorter (when compared to mediopunctatum). The twin brown bands on the femora of the nymphs should also help to separate them from modestum and mediopunctatum (usually three or four in those species).

The brown posterior margins and median dorsal stripes of the duns (similar to those found in M. vicarium) are typical of ithaca. In McDunnough’s original description of mediopunctatum (1926), he mentions that some of his (paratype) specimens were reared from subimagos, and he describes those subimagos as “quite pale whitish in coloration.”

Size might also be somewhat helpful in distinguishing these specimens from M. m. mediopunctatum (about 7-10 mm at maturity) and modestum (about 8-11 mm at maturity). M. ithaca is about 9-14 mm at maturity. The relatively mature nymph (#764) is at least 11 mm, the female dun (#733) is about 13 mm, and the male dun (#765) is about 11 mm.

When all of these factors are considered, it seems to me that M. ithaca is a more likely ID for the Eastern specimens. (See Bednarik and McCafferty 1979 and Lewis 1974.) I would suggest the following placement for specimens currently in this section:

M. ithaca nymph: http://www.troutnut.com/specimen/764

M. ithaca female dun: http://www.troutnut.com/specimen/733

M. ithaca male dun: http://www.troutnut.com/specimen/765

M. mediopunctatum arwini nymph: http://www.troutnut.com/specimen/573

M. mediopunctatum arwini nymph: http://www.troutnut.com/specimen/574

Best,

Lloyd

In this section, the Midwestern nymphs (#573 & #574) with the dark irregular ventral bars across the anterior portion of the sternites look like Maccaffertium mediopunctatum arwini (the Midwestern ssp.), but the two Eastern duns (#733 & #765) and the associated shuck (of #765) and nymph (#764) look more like Maccaffertium ithaca to me.

Three Maccaffertium species can have very similar ventral markings in the nymph—dark, sinuate, chevron-shaped bars on many of the sternites and dark lateral marks (sometimes connected to form an inverted U-shaped mark) on segment 9. The Eastern mediopunctatum subspecies, M. m. mediopunctatum, has these markings, as does M. ithaca. Similar markings also appear as a less-common variant marking of M. modestum (or the M. modestum species complex). However, these species differ in the length and location of posterolateral projections, leg markings, the appearance of the subs and adults, and size.

Although interpretation of posterolateral projections can be tricky, those projections should help to separate the nymph (and husk) from mediopunctatum. On mediopunctatum, projections are usually on segments 3-9, 4-9, or 5-9, and those on 8 and 9 are fairly long. On ithaca, projections are usually on segments 6-9 or 7-9, and those on 8 and 9 are somewhat shorter (when compared to mediopunctatum). The twin brown bands on the femora of the nymphs should also help to separate them from modestum and mediopunctatum (usually three or four in those species).

The brown posterior margins and median dorsal stripes of the duns (similar to those found in M. vicarium) are typical of ithaca. In McDunnough’s original description of mediopunctatum (1926), he mentions that some of his (paratype) specimens were reared from subimagos, and he describes those subimagos as “quite pale whitish in coloration.”

Size might also be somewhat helpful in distinguishing these specimens from M. m. mediopunctatum (about 7-10 mm at maturity) and modestum (about 8-11 mm at maturity). M. ithaca is about 9-14 mm at maturity. The relatively mature nymph (#764) is at least 11 mm, the female dun (#733) is about 13 mm, and the male dun (#765) is about 11 mm.

When all of these factors are considered, it seems to me that M. ithaca is a more likely ID for the Eastern specimens. (See Bednarik and McCafferty 1979 and Lewis 1974.) I would suggest the following placement for specimens currently in this section:

M. ithaca nymph: http://www.troutnut.com/specimen/764

M. ithaca female dun: http://www.troutnut.com/specimen/733

M. ithaca male dun: http://www.troutnut.com/specimen/765

M. mediopunctatum arwini nymph: http://www.troutnut.com/specimen/573

M. mediopunctatum arwini nymph: http://www.troutnut.com/specimen/574

Best,

Lloyd

Stenonema femoratum male spinner

3 replies

Last reply on May 21, 2012 by Entoman

Added more Heptagenia culacantha info

12 replies

Posted by Troutnut on Dec 19, 2006 in the species Heptagenia culacantha

Last reply on Feb 8, 2012 by Entoman

I went to the entomology library today and photocopied the 1985 paper that first described this curious species. I've updated the culacantha page with this information.

Red Heptagenia?

30 replies

Last reply on Jul 23, 2011 by PaulRoberts

The gills and protruding mouthparts make me think that this might be Cinygmula. I've seen red phase Rhithrogena nymphs, but have never seen this coloration in Cinygmula (or Heptagenia).

Start a Discussion of Heptageniidae

References

- Arbona, Fred Jr. 1989. Mayflies, the Angler, and the Trout. Nick Lyons Books.

- Jacobus, L. M., Wiersema, N.A., and Webb, J.M. 2014. Identification of Far Northern and Western North American Mayfly Larvae (Insecta: Ephemeroptera), North of Mexico; Version 2. Joint Aquatic Science meeting, Portland, OR. Unpublished workshop manual. 1-176.

- Needham, James G., Jay R. Traver, and Yin-Chi Hsu. 1935. The Biology of Mayflies. Comstock Publishing Company, Inc.

Mayfly Family Heptageniidae (March Browns, Cahills, Quill Gordons)

Taxonomy

Genus in Heptageniidae

Afghanurus

1

14

Anepeorus

0

0

CinygmaWestern Light Cahills

4

24

CinygmulaDark Red Quills

41

262

EcdyonurusWestern Ginger Quills

3

19

EpeorusLittle Maryatts

58

357

Heptagenia

10

44

Ironodes

1

3

Leucrocuta

11

58

Macdunnoa

0

0

Nixe

0

0

Raptoheptagenia

0

0

Rhithrogena

31

171

Spinadis

0

0

StenacronLight Cahills

8

47

StenonemaMarch Browns and Cahills

66

329

Genus in Heptageniidae: Afghanurus, Anepeorus, Cinygma, Cinygmula, Ecdyonurus, Epeorus, Heptagenia, Ironodes, Leucrocuta, Macdunnoa, Nixe, Raptoheptagenia, Rhithrogena, Spinadis, Stenacron, Stenonema