Hex Mayflies

Hexagenia limbata

The famous nocturnal Hex hatch of the Midwest (and a few other lucky locations) stirs to the surface mythically large brown trout that only touch streamers for the rest of the year.

Mayfly Species Ephemerella invaria (Sulphurs)

Ephemerella invaria is one of the two species frequently known as Sulphurs (the other is Ephemerella dorothea). There used to be a third, Ephemerella rotunda, but entomologists recently discovered that invaria and rotunda are a single species with an incredible range of individual variation. This variation and the similarity to the also variable dorothea make telling them apart exceptionally tricky.

As the combination of two already prolific species, this has become the most abundant of all mayfly species in Eastern and Midwestern trout streams.

Where & when

The invaria hatch begins in early May in Pennsylvania. The Catskills peak in late May and early June, while mid-June is best in the Adirondacks and the northern fringe of the Upper Midwest.Good fishing from this hatch usually lasts about two weeks in a particular location.

In 61 records from GBIF, adults of this species have mostly been collected during June (43%), May (28%), April (15%), and July (10%).

In 37 records from GBIF, this species has been collected at elevations ranging from 20 to 2559 ft, with an average (median) of 600 ft.

Species Range

Hatching behavior

Emergence itself takes quite a while, making emerger patterns more important for this hatch than for most. This importance is heightened by the lower availability of the fully formed duns. These duns take to the air more quickly than most of their Ephemerella kin, but anglers should still be prepared to imitate them if need be.

Spinner behavior

Time of day: Dusk

Habitat: Riffles

Knopp & Cormier write in Mayflies: An Angler's Study of Trout Water Ephemeroptera that the males seldom fall spent on the water and the females only fall sometimes. Ted Fauceglia's Mayflies says both genders fall spent on the water. This disagreement mirrors the confusion I've felt about this species on the stream; the spinners are generally unpredictable, but they can provide excellent fishing.

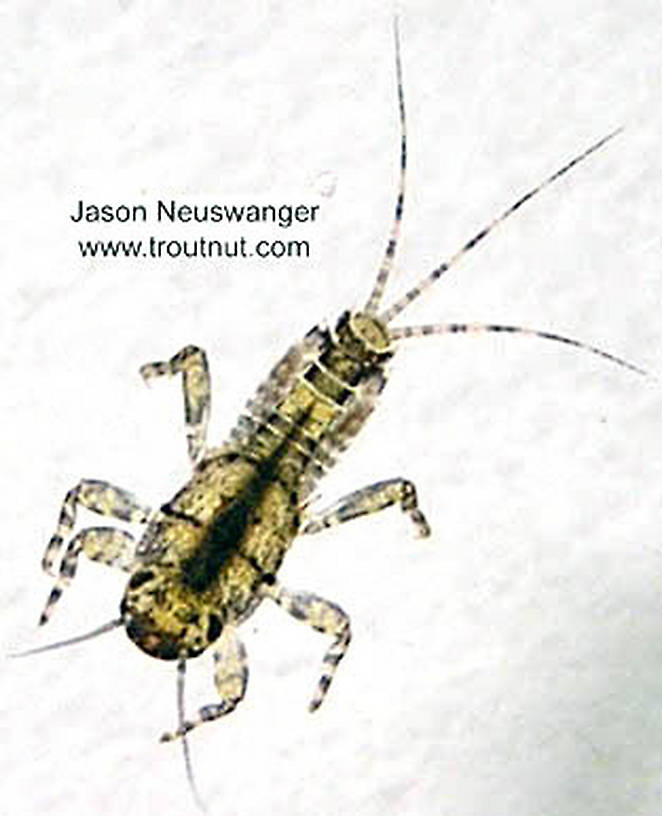

Nymph biology

Current speed: Usually medium to fast, sometimes slow

Substrate: Many types, but gravel is preferred

Environmental tolerance: Unlike Ephemerella subvaria, invaria is very tolerant of a wide range of conditions.

In the days and hours before the hatch these nymphs become especially active, so their imitation is especially useful. They clamber to better emergence sites where they rest in plain view of both trout and photographers (see my underwater photos). They also make apparent "practice runs" to and from the surface in the manner of Ephemerella subvaria.

The nymphs are a little bit difficult to recognize because they their base color ranges from brown to olive and they're adorned with many possible color patterns. Anglers should be prepared with imitations in brown and olive, hook sizes 12 through 16.

Ephemerella invaria Fly Fishing Tips

Take extra care during emergence to figure out if the trout are feeding on floating nymphs, emergers, or duns, and what size Sulphur they are taking. The invaria duns can be hook size 14 or 16. The possibility of confusing them with the smaller Ephemerella dorothea adds to the Sulphur challenge. Remember that the solution to this puzzle may vary from fish to fish, and you should switch flies or switch fish quickly if what you're trying isn't working.Physical description

Most physical descriptions on Troutnut are direct or slightly edited quotes from the original scientific sources describing or updating the species, although there may be errors in copying them to this website. Such descriptions aren't always definitive, because species often turn out to be more variable than the original describers observed. In some cases, only a single specimen was described! However, they are useful starting points.

Male Spinner

Wing length: 8-10 mm

A species of the Ephemerella invaria group; genitalia much as in E. rotunda (now a synonym of E. invaria); venation pale.

Eyes of male probably orange, in life. Head and thorax light reddish brown; pronotum shaded with smoky. Mesosternum rather deeper reddish brown. Legs pale whitish. Wings hyaline; venation pale; stigmatic area opaque whitish. Dorsum of abdomen light smoky to purplish brown; basal tergites darker than the apical ones. Posterior margins rather dark smoky brown; pleural fold yellowish. Ventrally pale yellowish white, the middle sternites semi-translucent; apical sternites opaque, yellowish. Tails white; joinings purplish black, very distinct. Genitalia very similar to rotunda, but with somewhat fewer spines on the penes.

Described as E. fratercula

Body length 7 mm, wing length 8 mm

A species of the Ephemerella invaria group; numerous ventral spines in the apical area of the penes; venation wholly pale. Nymph unknown.

Eyes reddish brown. Head light yellow; vertex shaded with brown. Prothorax smoky brown. Mesonotum light yellow; pleura and sternum deeper yellow; brown shading at bases of wings. Legs light yellow; femur of fore leg deeper yellow than tibia and tarsus, which are slightly darker than the middle and hind legs. Wings hyaline; venation wholly hyaline; cross veins indistinct except in the stigmatic area. Dorsum of abdomen deep smoky brown on the basal and middle tergites, lighter yellowish brown apically; basal tergites deeper smoky than middle ones. Posterior margins narrowly blackish brown. Venter light yellow, the apical sternites opaque and slightly deeper yellow; ganglionic areas smoky brown; no reddish brown shading, as in Ephemerella subvaria. Forceps as in Ephemerella invaria; numerous ventral spines on the apical area of the penes (see fig. 152). Tails pale, the joinings narrowly dark brown.

Described as E. rotunda

Body length 10 mm, wing length 10 mm

A species of the Ephemerella invaria group; venation pale; spines on the penes more numerous than in E. invaria and Ephererella subvaria; nymph dark brown with many fine pale dots, the dorsal spines better developed than in invaria.

Eyes probably orange in life. Head yellowish, shaded with reddish on the occiput. Antennae pale. Thorax light reddish yellow; pronotum shaded with purplish black. A dark brown area on each side of the mesonotum and two narrow blackish submedian streaks anterior to the scutellum. A dark brown line above each of the middle and hind legs; pleural sutures narrowly brown. Legs pale whitish. Wings hyaline; venation very pale yellowish to hyaline; stigmatic area rather opaque white.

Abdominal tergites pale yellowish, each with a broad purplish brown transverse band across the middle. On tergites 1-2 and 8-9, this dark band occupies most of the sclerite. Pleural fold pale. Traces of a pale median line, most distinct on the middle tergites. Ventrally yellowish white, sometimes with faint indications of yellowish brown transverse bands across the middle of each sternite, similar to those on the tergites. Oblique submedian streaks at the anterior margin of each sternite; may be rather indistinct. Tails white, basal joinings distinctly purplish black; beyond the middle these are but faintly indicated. Spines on the penes rather more numerous than in invaria: two small clusters of ventral spines are present, which are not found in invaria. Two to four apical spines are usually present (see fig. 152).

Described as E. vernalis

Body length 9-9.5 mm, wing length 8-10 mm

A species of the Ephemerella invaria group; the second joint of the forceps enlarged distally; venation yellowish to yellowish brown; usually 7 spines only, on penes.

Head light brown; eyes light orange. Thorax brown; pronotum often with a median pale streak; pleura marked with pale yellow; mesonotal scutellum margined with dark reddish brown. Ventrally brown, darkest at the center of the mesosternum. Fore leg yellowish to light brown; purplish streaks on distal portion of femur. Middle and hind legs very similar. Venation very light yellowish brown, the main veins of the costal border yellowish basally. Stigmatic area opaque.

Abdominal tergites 2-7 light purplish brown with a narrow median whitish line; 2-4 washed with brownish, 5-7 paler; posterior margins dark brown, postero-lateral angles and intersegmental rings greyish white; a purplish line margins the pale pleural fold. Tergites 8-10 washed with yellowish brown; a median light brown line is present, and a brownish patch on each side; one or more short dark dots near each stigma. Sternites 1-5 greyish, lavender tinged; 6-9 yellowish brown; on each, a brown line margins the pleural fold, less distinct on 6-9. Posterior margins and ganglionic areas whitish. Tails greyish to light brown, joinings purplish brown. Penes with fewer spines than E. rotunda (now a synonym of Ephemerella invaria), usually only 7, occasionally 10; of these, two may be apical in position, but more often there are no apical spines (see fig. 152).

Nymph

The nymph is smaller than rotunda (now a synonym for Ephemerella invaria); the dorsal abdominal spines are very poorly developed, and may be almost obsolescent. The color varies from pale yellowish brown heavily sprinkled with brown dots, to specimens which are almost wholly brown with yellowish brown dots. In the paler forms, the brown dots may be distributed rather uniformly, or may be arranged in bands across the anterior portion of the pronotum and between the roots of the wing pads on the mesonotum. Large pale lateral patches may be present on tergites 5 and 6; these patches may run together to form an almost wholly white dorsal area. The pale dots at the location of the dorsal spines are often present, as in E. rotunda.

Described as E. rotunda

The nymph is larger than Ephemerella invaria or Ephemerella subvaria; it is dark reddish brown in color, sprinkled with numerous very small pale dots. Each corner of the pronotum is pale. There are usually other smaller pale areas on each side of the pronotum, including a crescentic mark and two small round spots between this and the median line. Eight to ten somewhat larger pale areas are usually present on the mesonotum, between and anterior to the wing roots. Rather large pale lateral areas may be present on tergites 5 and 6; these may be connected along the anterior margin. Near the middle of each lateral extension is a dark bar. Venter somewhat paler than the dorsum; darkest on the apical sternites and the lateral portions of the middle ones. Traces of a pale median triangle at the anterior margin may be present on the middle and apical sternites. Tails yellowish brown; crossed by two or three dark bands near the middle, and another apically. White spots are present on each tergite, at the base of each dorsal spine. These spines are better developed than in invaria, but less prominent than in subvaria.

Described as E. vernalis

Nymphs resembling E. rotunda (now a synonym of Ephemerella invaria), but less robust. Vary in color from light yellowish brown to dark mahogany; body finely dotted and mottled with numerous small yellowish dots. Legs barred with yellow. A median yellowish dorsal streak is often present on the dorsum of the abdomen. Minute paired dorsal spines are present, and a whitish spot marks the base of each spine. Lateral extensions of the abdomen are more rounded on the outer margin than in rotunda; end spines not incurved; each lateral extension is crossed by a black streak. Indications of a yellowish mid-ventral line and a dark lateral line near the margin; posterior segments usually darker than the preceding ones.

Specimens of the Mayfly Species Ephemerella invaria

7 Male Duns

5 Female Duns

3 Male Spinners

3 Female Spinners

27 Nymphs

2 Streamside Pictures of Ephemerella invaria Mayflies:

15 Underwater Pictures of Ephemerella invaria Mayflies:

Discussions of Ephemerella invaria

I got my master’s degree under Ed Cooper at Penn State in 1966. I studied the impact of low oxygen from Penn State’s sewage plant on the mayflies of Spring Creek. The plant mostly removed BOD (organic matter which causes low oxygen) by oxidizing it in a bacteria rich environment. But at that time the plant did not remove phosphorus (and nitrogen) which fertilized the macrophytic algae and other plant growth. There were far more macrophytes (large plants) in Spring Creek below the sewage plant entrance than above, and essentially no mayflies. What was there in the effluent that killed the mayflies? Mayflies put directly in the effluent did not die over a 16 hour day. But oxygen samples taken over 24 hours in summer showed a much greater variation below the effluent (from 16 ppm (or mg/l), 160% of saturation in late afternoon) to 3 ppm (30 percent saturation just before dawn) (vs 14 to 10 ppm, +- 20 percent saturation above the effluent.

I built a Rube Goldberg machine in the lab that would control the oxygen levels and temperature of control and experimental cages that each held 25 mayflies. The control would keep oxygen near saturation and the experimental one would lower the oxygen over 8 hours (the length of night in summer). Mortality was dependent upon both oxygen level and temperature. Virtually no mayflies would die if the oxygen was above 2 PPM (or mg/l) at 8 C, or at 4.5 at 20 C. Seventy five percent of larvae would die at 1 ppm at 8 degrees and 2.5 ppm at 20 degrees. So the mortality was much more if the temperatures were high. Hence most of the mortality would presumably occur in August when the high temperatures (20C) would increase the larvae metabolism and hence need for oxygen, but the water would hold less oxygen even before the night-time respiration of the macrophytes would reduce it much further (to only 3 ppm). Thus the low nighttime oxygen caused by excessive plant growth was a sufficient cause or the near total absence of mayflies below the sewage plant. Recognizing the aquatic impact Penn State started to use land disposal of its effluent which as far as I knew alleviated, and even stopped, the negative impacts on the mayflies. Can anyone verify this ? The otherwise well done “The Fishery of Spring Creek; A Watershed Under Siege “

By Robert F. Carline, Rebecca L. Dunlap Jason E. Detar, Bruce A. Hollender Has nothing on dissolved oxygen or aquatic insects. In my opinion we need much more of an ecosystems approach for streams (Which we are doing for Little Sandy Creek in N.Y.).

Now back to Ephemeralla subvaria. The title of the paper I published on this project (my first of nearly 300 publications) was:

1. Hall, C.A.S. 1969. Mortality of the mayfly nymph, Ephemerella rotunda, at low dissolved oxygen concentrations. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 85(1): 34-39 (M.S. Thesis, Pennsylvania State University, 1966).

Whoa! Ephemeralla rotunda? This was by far the most abundant mayfly in Spring Creek where I sampled! But I could not even find the name in your list. Also I had my samples verified by Burke, author of the authoritative "Mayflies of Illinois", and he said Well that’s what it keyed out to in my book”. (Talk about scientific ass covering! ) Well to make matters worse (as of 24 hours ago) my next girlfriend, Molly, at the University of North Carolina, loved the name of “Ephemerella rotunda”, the rotund one, which comes to think of it described her as well. I liked it too. But n’exist plus: where had the most abundant mayfly gone? Fortunately upon reading the rest of the post I found “Ephemerella invaria is one of the two species frequently known as Sulphurs (the other is Ephemerella dorothea). There used to be a third, Ephemerella rotunda, but entomologists recently discovered that invaria and rotunda are a single species with an incredible range of individual variation." Ahh neither rotunda nor Molly stood the test of time. So I assume what I called rotunda is still alive and well in Spring Creek as invaria. Again, can anyone verify that?

If anyone wants to follow up on the distribution and abundance of mayfly (or any other species) may I recommend: Hall, C.A.S., J.A. Stanford and R. Hauer. 1992. The distribution and abundance of organisms as a consequence of energy balances along multiple environmental gradients. Oikos 65: 377-390. I can send it if you cannot get it from google, which I think you can. (chall@esf.edu)

Start a Discussion of Ephemerella invaria

References

- Arbona, Fred Jr. 1989. Mayflies, the Angler, and the Trout. Nick Lyons Books.

- Caucci, Al and Nastasi, Bob. 2004. Hatches II. The Lyons Press.

- Fauceglia, Ted. 2005. Mayflies . Stackpole Books.

- Knopp, Malcolm and Robert Cormier. 1997. Mayflies: An Angler's Study of Trout Water Ephemeroptera . The Lyons Press.

- Leonard, Justin W. and Fannie A. Leonard. 1962. Mayflies of Michigan Trout Streams. Cranbrook Institute of Science.

- Needham, James G., Jay R. Traver, and Yin-Chi Hsu. 1935. The Biology of Mayflies. Comstock Publishing Company, Inc.

- Swisher, Doug and Carl Richards. 2000. Selective Trout. The Lyons Press.

Mayfly Species Ephemerella invaria (Sulphurs)

Species Range

Common Names

Resources

- NatureServe

- Integrated Taxonomic Information System

- Global Biodiversity Information Facility

- Described by Walker (1853)