Hex Mayflies

Hexagenia limbata

The famous nocturnal Hex hatch of the Midwest (and a few other lucky locations) stirs to the surface mythically large brown trout that only touch streamers for the rest of the year.

Featured on the forum

Troutnut is a project started in 2003 by salmonid ecologist Jason "Troutnut" Neuswanger to help anglers and

fly tyers unabashedly embrace the entomological side of the sport. Learn more about Troutnut or

support the project for an enhanced experience here.

Mayfly Genus Rhithrogena

This genus is widespread across the country, but it is only of major importance to anglers in the West.

The best hatches come from Rhithrogena morrisoni, Rhithrogena hageni, and Rhithrogena undulata. Even the less common species , Rhithrogena futilis, and Rhithrogena robusta are probably more important than any of their Eastern counterparts.

The East/Midwest species are Rhithrogena jejuna, Rhithrogena manifesta, and Rhithrogena impersonata, which is arguably the most important of a minor group. All of them are widespread and none of them are abundant except in rare locations, mostly in Michigan and Wisconsin.

The best hatches come from Rhithrogena morrisoni, Rhithrogena hageni, and Rhithrogena undulata. Even the less common species , Rhithrogena futilis, and Rhithrogena robusta are probably more important than any of their Eastern counterparts.

The East/Midwest species are Rhithrogena jejuna, Rhithrogena manifesta, and Rhithrogena impersonata, which is arguably the most important of a minor group. All of them are widespread and none of them are abundant except in rare locations, mostly in Michigan and Wisconsin.

Genus Range

Hatching behavior

Most evidence points to Rhithrogena species emerging underwater. They usually do so on the stream bottom and float all the way to the surface as duns, but those emerging from slow water will rise most of the way as nymphs before struggling free of their shucks. How slow is slow? Depth and temperature are also suspected of playing a role, so whether to fish a nymph, a sunken emerger or dun imitating wet fly usually remains open to experimentation in any given hatch situation.Nymph biology

Current speed: fast to moderate

Substrate: cobble riffles, rapids, and runs

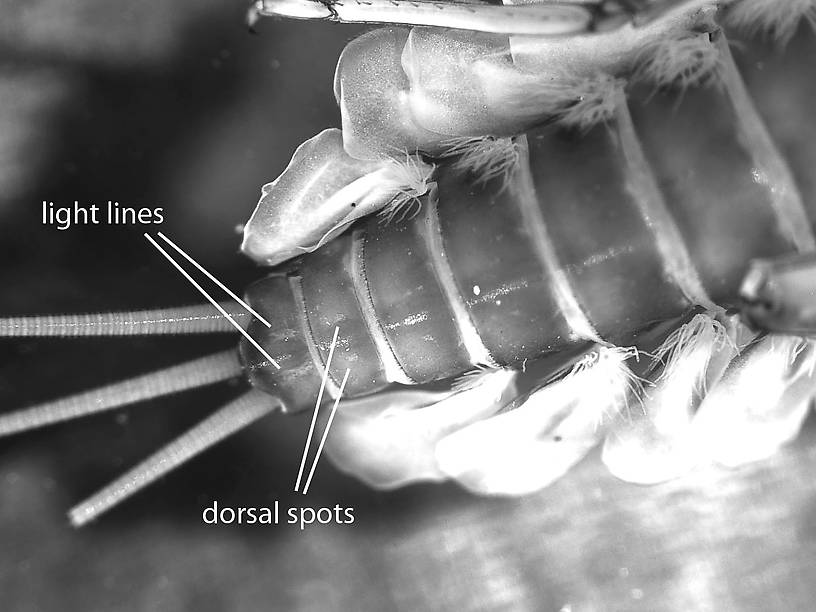

They have been portrayed strangely in angling texts, to the extent that they are hard to recognize when first observed in the wild. Many book illustrations show the gills fully spread out and opaque, giving the nymphs an exaggerated ovoid shape. Perhaps because it's hard to draw them any other way in pencil. But this really misrepresents the actual insects; you have to look pretty closely to notice the gill extensions under the body. They are very translucent and easy to miss. In the natural state their transluscent gills are also held much closer to their bodies. These drawings also show short, robust, crab-like body shapes, perhaps to somehow emphasize their proficiency as clingers. This further exacerbates the misconception. They are great clingers, but their bodies are more narrow and streamlined than drawings indicate, as demonstrated in the photos below.

Specimens of the Mayfly Genus Rhithrogena

2 Male Duns

2 Female Duns

12 Male Spinners

4 Female Spinners

11 Nymphs

Discussions of Rhithrogena

Clinger nymphs are shaped that way to hang in really fast currents. Really?

14 replies

Posted by Entoman on Feb 23, 2013

Last reply on Jun 14, 2017 by Steamntrout

It is commonly held that clingers are flattened to make their lives better adapted to faster water. Their teardrop shape is certainly a classic symbol of aero and hydrodynamic perfection, so there must be some connection, right? It seems to me that such ideas show a complete misunderstanding of the hydraulic reality in which they live. Current is negligable even in the fastest a few mm. from the surface of solid objects. In fact, it is actually quite calm. I've observed baetids clinging by their tippy toes to the tops of rocks in fast riffles with no apparent effort, often next to clinger species that look like they're hanging on for dear life. What if clinger nymphs are flattened not to hold their place in fast currents but rather to facilitate movement in their ecological niche of the cramped spaces under and between cobble or crevices in other substrate types?

It is also thought that the gills of some species form ''suction'' to hold them in place. Since suction is a phenomena of vacuum creation in the atmosphere, how are these nymphs accomplishing this underwater? Is it their ultra delicate gills that hold them in place or a firm claw grip? The horizontal sprawl of the legs masks this as the gills stay in place until the legs brake free. Exposed to the air, the gills seem to laminate against the rock, just as crepe paper would if first held underwater before a rock was lifted out into the air from underneath it. However, underwater their gills behave like the crepe, flowing freely. They are performing their function as gills not suction cups. I find it hard to believe they evolved the way some think merely so they can make it more difficult for humans to pluck them from rocks in the atmosphere. How is it these mighty structures that defy our attempts to pry them from the rocks curiously fall off so easily when prodded for inspection a few seconds later in a tray or jostled in a container on the way home?

Even many scientific papers have encouraged these dubious beliefs so it's not just angler myth... And they go unchallenged... Thoughts?

It is also thought that the gills of some species form ''suction'' to hold them in place. Since suction is a phenomena of vacuum creation in the atmosphere, how are these nymphs accomplishing this underwater? Is it their ultra delicate gills that hold them in place or a firm claw grip? The horizontal sprawl of the legs masks this as the gills stay in place until the legs brake free. Exposed to the air, the gills seem to laminate against the rock, just as crepe paper would if first held underwater before a rock was lifted out into the air from underneath it. However, underwater their gills behave like the crepe, flowing freely. They are performing their function as gills not suction cups. I find it hard to believe they evolved the way some think merely so they can make it more difficult for humans to pluck them from rocks in the atmosphere. How is it these mighty structures that defy our attempts to pry them from the rocks curiously fall off so easily when prodded for inspection a few seconds later in a tray or jostled in a container on the way home?

Even many scientific papers have encouraged these dubious beliefs so it's not just angler myth... And they go unchallenged... Thoughts?

Start a Discussion of Rhithrogena

References

- Arbona, Fred Jr. 1989. Mayflies, the Angler, and the Trout. Nick Lyons Books.

- Caucci, Al and Nastasi, Bob. 2004. Hatches II. The Lyons Press.

- Knopp, Malcolm and Robert Cormier. 1997. Mayflies: An Angler's Study of Trout Water Ephemeroptera . The Lyons Press.

- Leonard, Justin W. and Fannie A. Leonard. 1962. Mayflies of Michigan Trout Streams. Cranbrook Institute of Science.

- Needham, James G., Jay R. Traver, and Yin-Chi Hsu. 1935. The Biology of Mayflies. Comstock Publishing Company, Inc.

Mayfly Genus Rhithrogena

Taxonomy

Species in Rhithrogena

Rhithrogena amica

0

0

Rhithrogena anomala

0

0

Rhithrogena brunneotincta

0

0

Rhithrogena exilis

0

0

Rhithrogena fasciata

0

0

Rhithrogena flavianula

0

0

Rhithrogena fuscifrons

0

0

Rhithrogena futilisWestern Gordon Quills

0

0

Rhithrogena gaspeensis

0

0

Rhithrogena hageniWestern Black Quills

6

62

Rhithrogena impersonataDark Red Quills

3

19

Rhithrogena jejunaDark Red Quills

0

0

Rhithrogena manifesta

0

0

Rhithrogena morrisoniWestern March Browns

4

16

Rhithrogena robusta

2

5

Rhithrogena uhari

0

0

Rhithrogena undulataSmall Western Red Quills

2

18

Rhithrogena virilis

6

32

Species in Rhithrogena: Rhithrogena amica, Rhithrogena anomala, Rhithrogena brunneotincta, Rhithrogena exilis, Rhithrogena fasciata, Rhithrogena flavianula, Rhithrogena fuscifrons, Rhithrogena futilis, Rhithrogena gaspeensis, Rhithrogena hageni, Rhithrogena impersonata, Rhithrogena jejuna, Rhithrogena manifesta, Rhithrogena morrisoni, Rhithrogena robusta, Rhithrogena uhari, Rhithrogena undulata, Rhithrogena virilis

5 species (Rhithrogena decora, Rhithrogena ingalik, Rhithrogena notialis, Rhithrogena plana, and Rhithrogena rubicunda) aren't included.