Blue-winged Olives

Baetis

Tiny Baetis mayflies are perhaps the most commonly encountered and imitated by anglers on all American trout streams due to their great abundance, widespread distribution, and trout-friendly emergence habits.

Featured on the forum

This seems to be a young larva of Limnephilus. Although not clear in the picture, several ventral abdominal segments have chloride epithelia.

Troutnut is a project started in 2003 by salmonid ecologist Jason "Troutnut" Neuswanger to help anglers and

fly tyers unabashedly embrace the entomological side of the sport. Learn more about Troutnut or

support the project for an enhanced experience here.

By Dneuswanger on September 5th, 2014

This was the final day of a five-day, father-son fishing trip to south-central Alaska. Jason and I awakened to sunny skies at the Swiss Alaska Inn in Talkeetna. While enjoying breakfast in their fine restaurant, we checked out some Denali flight tour brochures. McKinley Tours with K2 Aviation had one route called the “Grand Tour” that would provide high-altitude views in relatively clear skies without ascending all the way to the summit, which was still shrouded in clouds. Luckily, they had room for a couple “walk-on” passengers for the tour that departed at 10:30 a.m., so we booked it. I elected not to inform my wife, Sandy, of our plans before the flight, judging that she had enough to worry about at home after a September 4 windstorm in NW Wisconsin had dropped a couple large trees on our attached garage roof.

Our pilot and guide, Rick, was professional, knowledgeable, and had a good sense of humor, so he inspired confidence and provided entertaining narrative the entire 1.5-hour flight. Jason and I sat in the rear-most seats of the twin-engine, ten-seat plane, enjoying more legroom and greater lateral vision than the other five passengers because we were far behind the wings.

Shortly after take-off, we flew over the highly braided channels of the converging Talkeetna, Chulitna, and Susitna rivers.

Within 15 minutes were entering the foothills of the Alaska Range. And before long we were viewing glaciers, sheer rock faces, and craggy peaks.

I was amazed at the effects of gravity on rock and ice. There were large piles of rubble atop the snow and ice at the base of many sheer rock faces. And there were huge, gaping crevasses arrayed in interesting patterns wherever a glacier flowed over uneven terrain. These highly variable breaks in snow/ice cover had not yet filled with new snow, so it was easy to see what dangerous obstacles they must present to those who would attempt to traverse them while climbing up and down the mountain. From our altitude, we could see the effects of friction along the side walls of the valleys through which these massive ice sheets flowed, giving the crevasses a crescent shape with convex centers leading the way downhill. They appeared even wider toward the middle wherever the ice spilled over a particularly steep ledge.

We observed the lateral moraines formed at the edges of ice sheets and the dirty medial moraines formed by the joining of lateral moraines of glaciers descending from adjacent valleys.

Ascending through various passes, we were treated to clear views of the summits of Mount Hunter and Mount Foraker. In a small plane surrounded by such grandeur, it was possible to understand what a camp-raiding raven might see while flying into this raw wilderness of rock and ice. Indeed, climbers sometimes return to food caches only to find that ravens have scattered them all over the ice and rock.

We saw the glaciated landing area where most Denali climbers are flown in, and we flew past a small amphitheater known by climbers as Camp 3. We also flew over the “Mountain House” – a cabin and outhouse flown in and built stick-by-stick on a small outcropping of rock in a glacier where planes can land. (Is this location the inspiration for “Mountain House” freeze-dried meals?)

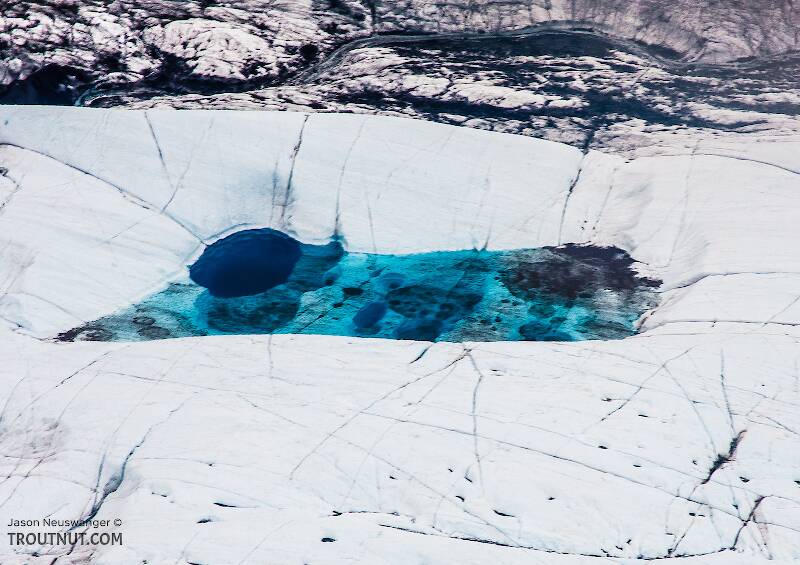

When I asked our pilot how they know the snow atop the glacier is firm enough to land, he said, “Well, normally the first flight of the day serves as the ‘guinea pig’ to determine that.” There have been several occasions when passengers had to exit the plane and pack down a “runway” with snowshoes so the plane could take off again. I’m glad we did not choose a flight that included a glacier landing. Occasionally we would fly over a glacial tarn – a small depression containing glacial melt-water reflecting a strikingly bright blue-green light. Our pilot called them “sapphires” because they resembled blue-green gems.

All in all, we got an eagle’s-eye view of a striking landscape that we would never have seen any other way. I came away with the impression that climbing these peaks would be a high-risk challenge that would not only be hard work, but would be miserably uncomfortable at times. The degree of suffering seems highly disproportional to the personal reward associated with achievement, especially the way groups are guided these days, where much of the hard, dangerous work is done by guides; and most reasonably fit people willing to suffer though the experience can reach the summit.

After the flight, we took a short drive through “downtown” Talkeetna, which was loaded with gift shops targeting cruise line visitors. We walked out on a well-trodden sandbar along the Susitna River, then bought some roasted almonds from an enterprising young girl before heading north to Fairbanks.

We drove at a leisurely pace while trying to catch a glimpse of the summit of Denali along the way. Twice we were fooled into thinking we may have seen it; but Jason confirmed later that we were seeing smaller snow-covered peaks in the foreground, including Mount Deception (where a group of senior tourists gushed over their good fortune in having finally “seen Denali”) and Mount Mather. Denali remained mysteriously cloaked in the high clouds.

We stopped outside Denali National Park and had a late lunch at the Alaska Salmon Bake Restaurant, arriving back in Fairbanks by ~7 p.m. after a spectacular day of sight-seeing.

Our pilot and guide, Rick, was professional, knowledgeable, and had a good sense of humor, so he inspired confidence and provided entertaining narrative the entire 1.5-hour flight. Jason and I sat in the rear-most seats of the twin-engine, ten-seat plane, enjoying more legroom and greater lateral vision than the other five passengers because we were far behind the wings.

Shortly after take-off, we flew over the highly braided channels of the converging Talkeetna, Chulitna, and Susitna rivers.

Within 15 minutes were entering the foothills of the Alaska Range. And before long we were viewing glaciers, sheer rock faces, and craggy peaks.

I was amazed at the effects of gravity on rock and ice. There were large piles of rubble atop the snow and ice at the base of many sheer rock faces. And there were huge, gaping crevasses arrayed in interesting patterns wherever a glacier flowed over uneven terrain. These highly variable breaks in snow/ice cover had not yet filled with new snow, so it was easy to see what dangerous obstacles they must present to those who would attempt to traverse them while climbing up and down the mountain. From our altitude, we could see the effects of friction along the side walls of the valleys through which these massive ice sheets flowed, giving the crevasses a crescent shape with convex centers leading the way downhill. They appeared even wider toward the middle wherever the ice spilled over a particularly steep ledge.

We observed the lateral moraines formed at the edges of ice sheets and the dirty medial moraines formed by the joining of lateral moraines of glaciers descending from adjacent valleys.

Ascending through various passes, we were treated to clear views of the summits of Mount Hunter and Mount Foraker. In a small plane surrounded by such grandeur, it was possible to understand what a camp-raiding raven might see while flying into this raw wilderness of rock and ice. Indeed, climbers sometimes return to food caches only to find that ravens have scattered them all over the ice and rock.

We saw the glaciated landing area where most Denali climbers are flown in, and we flew past a small amphitheater known by climbers as Camp 3. We also flew over the “Mountain House” – a cabin and outhouse flown in and built stick-by-stick on a small outcropping of rock in a glacier where planes can land. (Is this location the inspiration for “Mountain House” freeze-dried meals?)

When I asked our pilot how they know the snow atop the glacier is firm enough to land, he said, “Well, normally the first flight of the day serves as the ‘guinea pig’ to determine that.” There have been several occasions when passengers had to exit the plane and pack down a “runway” with snowshoes so the plane could take off again. I’m glad we did not choose a flight that included a glacier landing. Occasionally we would fly over a glacial tarn – a small depression containing glacial melt-water reflecting a strikingly bright blue-green light. Our pilot called them “sapphires” because they resembled blue-green gems.

All in all, we got an eagle’s-eye view of a striking landscape that we would never have seen any other way. I came away with the impression that climbing these peaks would be a high-risk challenge that would not only be hard work, but would be miserably uncomfortable at times. The degree of suffering seems highly disproportional to the personal reward associated with achievement, especially the way groups are guided these days, where much of the hard, dangerous work is done by guides; and most reasonably fit people willing to suffer though the experience can reach the summit.

After the flight, we took a short drive through “downtown” Talkeetna, which was loaded with gift shops targeting cruise line visitors. We walked out on a well-trodden sandbar along the Susitna River, then bought some roasted almonds from an enterprising young girl before heading north to Fairbanks.

We drove at a leisurely pace while trying to catch a glimpse of the summit of Denali along the way. Twice we were fooled into thinking we may have seen it; but Jason confirmed later that we were seeing smaller snow-covered peaks in the foreground, including Mount Deception (where a group of senior tourists gushed over their good fortune in having finally “seen Denali”) and Mount Mather. Denali remained mysteriously cloaked in the high clouds.

We stopped outside Denali National Park and had a late lunch at the Alaska Salmon Bake Restaurant, arriving back in Fairbanks by ~7 p.m. after a spectacular day of sight-seeing.

Photos by Troutnut from Denali National Park, Miscellaneous Alaska, and the Susitna River in Alaska

Quick Reply

Related Discussions

Topic

Replies

Last Reply

15

Jun 29, 2015

by Corey

by Corey

41

Mar 20, 2011

by Aaron7_8

by Aaron7_8