Blue-winged Olives

Baetis

Tiny Baetis mayflies are perhaps the most commonly encountered and imitated by anglers on all American trout streams due to their great abundance, widespread distribution, and trout-friendly emergence habits.

Featured on the forum

This one seems to lead to Couplet 35 of the Key to Genera of Perlodidae Nymphs and the genus Isoperla, but I'm skeptical that's correct based on the general look. I need to get it under the microscope to review several choices in the key, and it'll probably end up a different Perlodidae.

Troutnut is a project started in 2003 by salmonid ecologist Jason "Troutnut" Neuswanger to help anglers and

fly tyers unabashedly embrace the entomological side of the sport. Learn more about Troutnut or

support the project for an enhanced experience here.

This topic is about the Mayfly Family Baetidae

"These little critters supplant the importance of many other well-known mayfly hatches."

-Fred Arbona in Mayflies, the Angler, and the Trout

Arbona did not overestimate these critters. Their great numbers and multiple broods each season make up for their size, which is rarely larger than size 16 and often smaller than size 20.

Hardly mentioned in angling literature prior to the middle of the last century, baetids have become increasingly important to anglers, rivaling any other family of mayflies in this regard. This is largely due to the extension of fishing seasons that now include the early and late periods when this family’s species usually dominate hatching activity. Another important reason is the tremendous improvement in tackle allowing more practical imitation of these little mayflies. The dramatic ecological changes in many of our watersheds and the subsequent impact this has had on the makeup of taxa populations is also a factor.

Common baetid hatches with a national distribution are the species Acentrella turbida, Baetis brunneicolor, and Baetis tricaudatus. In the West, Baetis bicaudatus, Diphetor hageni and Plauditus punctiventris can also be common. In the East and the Midwest, look for Baetis intercalaris and Plauditus dubius. The species Iswaeon anoka is important in both the West and Midwest. Some of the Procloeon and Anafroptilum (previously Centroptilum) species are coming to the increasing notice of anglers across the country.

Stillwater anglers are likely to run across Callibaetis ferrugineus ferrugineus in the East and Midwest. Western anglers will find Callibaetis californicus and Callibaetis ferrugineus hageni to be very important.

Streamside identification of these mayflies to the level of genus, let alone species, has always been difficult. It's a very rare angler who can correctly proclaim a mayfly to be "Baetis" at a glance and be right on purpose, rather than making a lucky (albeit likely) guess at that genus versus the many others in the family. This is now even more so as new taxonomic evidence has shown hind wing conformation (or lack of hind wings) and other features are less dependable as ways to tell the genera apart. Many of the lesser-known species probably produce excellent local hatches but have not caught enough attention to be properly recognized by anglers. The lesson is that we should not assume anything about the identity of many Baetidae hatches we come across; they may not even be in the Baetis genus, let alone familiar species.

Example specimens

PaulRoberts on Feb 1, 2012February 1st, 2012, 2:05 pm EST

Often the first fishing for bug-eaters I do every year is the early Baetis activity. Then…the Baetid activity just continues through the year on virtually all the waters I fish. This is probably so for you all too.

I often fish a Baetid dry ahead of a Baetid nymph, since individual fish could be targeting either. I fish the #18 or #20 nymph on a short (~18-24”) length of 7x to the bend of the hook of a #16 Parachute dry. A tiny daub of tungsten putty helps the short fine dropper break the surface film, as it’s critical to have the dropper line as straight as possible as soon as possible so I can detect every take. I use this combination all year and it's even a smart prospecting rig on waters calm enough to see the small dry.

For my bread-n-butter recipes I can be a pretty lazy tier, so I want as close to an instant tie as I can get. The following are two ~4 minute recipes:

Parafilm Baetid:

This pattern uses a single section of mallard flank barbs (tinted ahead of time with a swipe of a permanent marker) for both the tail and the legs, using the tips for the tail and the butts for the legs. Parafilm (laboratory thermo-plastic film) is used for the body, and tinted with permanent markers. The Parafilm body makes the fly sink a little quicker than dubbed ones, esp with a heavy iron (like the 3906 in this pic).

It’s important to me to have the fly drift correctly in the water, not flip upside down. So it needs an ample tail to right the hook when it’s tethered. Also, with the Parafilm body it helps to adjust the legs with thread so they angle upwards, so they are above the central plane of the fly. I take the most time on this fly with the legs so they are equal on each side in number, length, thickness, and orientation. No need to be anatomically correct so two legs to a side is enough to suggest legs. I suspect the upside down or rolling flies affect my catch rate, as I’ve had repeated refusals to such flies and then made good by tying on a fresh one.

(Yeah, I know there are 4 legs on the left side -I snipped off #3 after I noticed.)

Baetid #2:

The second pattern is similar to a combination of the “WD40” and "Kimball's Emerger", except that it doesn’t bother with the wingcase. The wingcase is suggested with permanent markers: a spot of dark brown behind the head, and two black wing-buds. Again the tinted duck flank for tail and legs, then olive thread for the abdomen, a pale pinkish-golden dubbing for the thorax. Legs equal again, but not so critical that they ride well above the central (dorsal/ventral) plane, as the dubbing adds some buoyancy. The legs should not hang below the plane or the fly will likely ride upside down.

{EDIT}: Just noticed this fly has the wingcase, but I usually just omit it.

I tie a few others too, but these cover the dropper nymph deal pretty well for me.

What Baetid nymph patterns do you rely on?

I often fish a Baetid dry ahead of a Baetid nymph, since individual fish could be targeting either. I fish the #18 or #20 nymph on a short (~18-24”) length of 7x to the bend of the hook of a #16 Parachute dry. A tiny daub of tungsten putty helps the short fine dropper break the surface film, as it’s critical to have the dropper line as straight as possible as soon as possible so I can detect every take. I use this combination all year and it's even a smart prospecting rig on waters calm enough to see the small dry.

For my bread-n-butter recipes I can be a pretty lazy tier, so I want as close to an instant tie as I can get. The following are two ~4 minute recipes:

Parafilm Baetid:

This pattern uses a single section of mallard flank barbs (tinted ahead of time with a swipe of a permanent marker) for both the tail and the legs, using the tips for the tail and the butts for the legs. Parafilm (laboratory thermo-plastic film) is used for the body, and tinted with permanent markers. The Parafilm body makes the fly sink a little quicker than dubbed ones, esp with a heavy iron (like the 3906 in this pic).

It’s important to me to have the fly drift correctly in the water, not flip upside down. So it needs an ample tail to right the hook when it’s tethered. Also, with the Parafilm body it helps to adjust the legs with thread so they angle upwards, so they are above the central plane of the fly. I take the most time on this fly with the legs so they are equal on each side in number, length, thickness, and orientation. No need to be anatomically correct so two legs to a side is enough to suggest legs. I suspect the upside down or rolling flies affect my catch rate, as I’ve had repeated refusals to such flies and then made good by tying on a fresh one.

(Yeah, I know there are 4 legs on the left side -I snipped off #3 after I noticed.)

Baetid #2:

The second pattern is similar to a combination of the “WD40” and "Kimball's Emerger", except that it doesn’t bother with the wingcase. The wingcase is suggested with permanent markers: a spot of dark brown behind the head, and two black wing-buds. Again the tinted duck flank for tail and legs, then olive thread for the abdomen, a pale pinkish-golden dubbing for the thorax. Legs equal again, but not so critical that they ride well above the central (dorsal/ventral) plane, as the dubbing adds some buoyancy. The legs should not hang below the plane or the fly will likely ride upside down.

{EDIT}: Just noticed this fly has the wingcase, but I usually just omit it.

I tie a few others too, but these cover the dropper nymph deal pretty well for me.

What Baetid nymph patterns do you rely on?

Martinlf on Feb 1, 2012February 1st, 2012, 4:23 pm EST

Thanks, Paul. I love fishing olives, and though most of my time is spent throwing a single dry fly, I want to fish the nymphs more. I had one very good day a few years back with what is basically an iron lotus pattern. I fished it solo, without split shot, as the tungsten bead provided enough weight. Fish hit it dead drifted and led slightly Czech nymph style. It's tied in the round, with no legs, though I have certainly tied legs on other nymphs. I'd like to try your dry and dropper technique this spring, and will favor your second tie, as I'm not at all sure where to get or how to work with Parafilm. Gonzo also has stated that nymphs that drift right side up work best in some conditions. He uses a bent hook and poly yarn wingcase to orient them. An article in Flyfisherman a while back also discussed this topic. Your comments on orienting the tails and legs make perfect sense to me.

"He spread them a yard and a half. 'And every one that got away is this big.'"

--Fred Chappell

--Fred Chappell

Entoman on Feb 1, 2012February 1st, 2012, 6:57 pm EST

Great post, Paul. I really like the top nymph.

"It's not that I find fishing so important, it's just that I find all other endeavors of Man equally unimportant... And not nearly as much fun!" Robert Traver, Anatomy of a Fisherman

PaulRoberts on Feb 2, 2012February 2nd, 2012, 8:03 am EST

Kurt, I’ve used Parafilm quite a lot. It makes one of the quickest (and beautifully translucent) midge and caddis larvae ties out there –although I’ve beaten my own speed records with other materials. It’s pretty durable too, when cold –as in trout water. It’s a translucent but slightly cloudy fleshy white in color that colors up with markers really well –allowing you to leave pale bellies. Because of its “lack of puffiness” it requires some design adjustments to get some of them to drift oriented upright, as mentioned. Check em in the bathtub before you take em to the stream.

The 2nd pattern was introduced to me by Joe Cambridge as the “Kimball’s Emerger“, although the Kimball’s is actually tied with a loose wingcase to be fished in the surface film. I first used the present nymph version on the Delaware in tandem with the dry for very touchy browns (and a couple brookies! –not the usual thing on the Big-D) that were taking 5 Baetid nymphs to every dun. The nymph on a short dropper allowed me to catch those selective and wary browns. Takes were so subtle in that calm water that they registered as tension in the dropper line, or simply by water movement; It was easy to miss them. I kept shortening my dropper when I realized just how light takers they were. The fly has worked in many circumstances since, but detection is critical and this requires deft control of the rig.

Louis,

Do try the dropper rig. Following are some important details so you aren’t frustrated with the learning curve in getting the most out of the rig. If you are willing to read, I'm willing to write. :)

I’m going to eventually leave the Baetids behind in this post too, because I find nymphing fascinating and love to share it. It’s the same game across the spectrum, but the Baetid patterns are at the delicate end of that spectrum, the stream simply having to allow you more to go on there in terms of useful water. No worries as trout, their available food, and our flies, share a common space -drift lanes.

First, I edited the OP a bit, realizing I wrote that I use Comparadun patterns where I meant to say Parachute patterns, which support the dropper better. The tail is important in that it is what supports the dropper first. If it sinks, your dry is severely compromised and won’t remain an indicator either, for long. Grease that tail and the first couple inches of dropper, which I then snug right up high near the tail. I’m going to experiment with a combo tail like Matt uses on his Comparaduns –using well splayed fibettes over antron –likely an improvement. There is also a guy who ties a loop of fine gel-spun polyester (poly braid line), which floats, into his indicator flies coming directly out the back end which add to the tail buoyancy, which he then loops or ties on the dropper. Nifty idea I’ve yet to try.

Fishing:

This rig is for targeting specific drift lanes (laminar flow) as turbulence (much slack in the dropper) will cause a disconnect between the dry and nymph, thwarting strike detection. The idea is to keep the dropper straight enough between dry and nymph that you can detect takes. So, first, a short fine dropper is important. The rig fishes better as the dropper gets wet, when it will sink out of the sticky surface film more readily, but again, grease the first couple inches to help the fly stay up. Fluorocarbon I felt sunk the tail of the dry fly too readily.

The proper cast places both flies in the exact same lane, and in line with each other; the nymph following right behind the dry. Ideally you want a bit of slack in the dropper so the surface film doesn't capture and skate it around. One way to do this is to get the nymph to splash down first –or at least not have the dry land first with the dropper landing somewhat taut where the surface film will likely capture it. This is easiest with a little weight on the dropper. Keeping the nymph wet helps too. Avoid throwing uncontrolled curves; If you are throwing curves – not controlling the nymph – you will not be catching fish on it and might as well just fish the dry alone. Standing directly below the feeding lane is the easiest position, and using the old “book under the arm” style helps keep the line leader and dropper staying in line.

If, on the drift, turbulence is creating too much slack in the dropper for detection, I add a tiny bit of tungsten putty or the tiniest of shot –which cures a lot of detection ills. I like the putty now bc it is so easy to work with: no dropping tiny shot with cold fingers, I can easily remove it or add more, and it can’t damage the fine dropper. With a heavy hook on the nymph you may not need to add weight to the dropper; See what the current allows. If good fish are taking duns real well, I may forgo the nymph. But a good proportion of the time, especially during sparser emergences, the better fish are more susceptible to the nymph than the dry, so it’s worth getting to know how to do it.

I mentioned this rig as a prospecting rig bc Baetids are so common, but it is not a general prospecting rig when factoring in the range of current types streams dish out. It helps to know where it can be put to good use. It is delicate enough that it requires smooth flow and really shines on calm water. If there is much turbulence it’s best to go up in dry fly size (often beyond Baetis size) for the buoyancy, so you can add weight to the dropper.

Still more turbulence? In my mind the dry/dropper deal hits diminished returns quickly. “Dead-drift” below the surface is not accomplished (in anything other than laminar flow) the same way it is with a dry fly, because strike detection is destroyed when you introduce the slack you need to get a natural drift with a dry. Instead, a nymph must be lead (pulled), as you mention, one way or another, even with an indicator (except possibly on really laminar flow, both horizontally across the lane and vertically, which is rarely offered by streams, (but more apt to be found in the more stable lowland rivers). Such spots DO exist on smaller waters, and recognizing laminar flow is key to catching. Sometimes they are rather large and long –“soft spots” I call them (coined by Tom Rosenbauer) - but most are discrete. Trout know them, as this is where they drift feed.

It is possible to attack the more turbulent (and deeper) spots by going up in shot weight, which then requires more buoyancy in the indicator, and a larger outfit to handle it. The difference does not appear to be linear, but exponential (to some unknown factor). I can indicator fish pretty “heavy” water when steelheading, but by then I’ve gone up to a 9wt outfit! For trout fishing, well before I need to break out the 9wt, I’ve dropped the indicators altogether, and fish heavier waters by feel.

The 2nd pattern was introduced to me by Joe Cambridge as the “Kimball’s Emerger“, although the Kimball’s is actually tied with a loose wingcase to be fished in the surface film. I first used the present nymph version on the Delaware in tandem with the dry for very touchy browns (and a couple brookies! –not the usual thing on the Big-D) that were taking 5 Baetid nymphs to every dun. The nymph on a short dropper allowed me to catch those selective and wary browns. Takes were so subtle in that calm water that they registered as tension in the dropper line, or simply by water movement; It was easy to miss them. I kept shortening my dropper when I realized just how light takers they were. The fly has worked in many circumstances since, but detection is critical and this requires deft control of the rig.

Louis,

Do try the dropper rig. Following are some important details so you aren’t frustrated with the learning curve in getting the most out of the rig. If you are willing to read, I'm willing to write. :)

I’m going to eventually leave the Baetids behind in this post too, because I find nymphing fascinating and love to share it. It’s the same game across the spectrum, but the Baetid patterns are at the delicate end of that spectrum, the stream simply having to allow you more to go on there in terms of useful water. No worries as trout, their available food, and our flies, share a common space -drift lanes.

First, I edited the OP a bit, realizing I wrote that I use Comparadun patterns where I meant to say Parachute patterns, which support the dropper better. The tail is important in that it is what supports the dropper first. If it sinks, your dry is severely compromised and won’t remain an indicator either, for long. Grease that tail and the first couple inches of dropper, which I then snug right up high near the tail. I’m going to experiment with a combo tail like Matt uses on his Comparaduns –using well splayed fibettes over antron –likely an improvement. There is also a guy who ties a loop of fine gel-spun polyester (poly braid line), which floats, into his indicator flies coming directly out the back end which add to the tail buoyancy, which he then loops or ties on the dropper. Nifty idea I’ve yet to try.

Fishing:

This rig is for targeting specific drift lanes (laminar flow) as turbulence (much slack in the dropper) will cause a disconnect between the dry and nymph, thwarting strike detection. The idea is to keep the dropper straight enough between dry and nymph that you can detect takes. So, first, a short fine dropper is important. The rig fishes better as the dropper gets wet, when it will sink out of the sticky surface film more readily, but again, grease the first couple inches to help the fly stay up. Fluorocarbon I felt sunk the tail of the dry fly too readily.

The proper cast places both flies in the exact same lane, and in line with each other; the nymph following right behind the dry. Ideally you want a bit of slack in the dropper so the surface film doesn't capture and skate it around. One way to do this is to get the nymph to splash down first –or at least not have the dry land first with the dropper landing somewhat taut where the surface film will likely capture it. This is easiest with a little weight on the dropper. Keeping the nymph wet helps too. Avoid throwing uncontrolled curves; If you are throwing curves – not controlling the nymph – you will not be catching fish on it and might as well just fish the dry alone. Standing directly below the feeding lane is the easiest position, and using the old “book under the arm” style helps keep the line leader and dropper staying in line.

If, on the drift, turbulence is creating too much slack in the dropper for detection, I add a tiny bit of tungsten putty or the tiniest of shot –which cures a lot of detection ills. I like the putty now bc it is so easy to work with: no dropping tiny shot with cold fingers, I can easily remove it or add more, and it can’t damage the fine dropper. With a heavy hook on the nymph you may not need to add weight to the dropper; See what the current allows. If good fish are taking duns real well, I may forgo the nymph. But a good proportion of the time, especially during sparser emergences, the better fish are more susceptible to the nymph than the dry, so it’s worth getting to know how to do it.

I mentioned this rig as a prospecting rig bc Baetids are so common, but it is not a general prospecting rig when factoring in the range of current types streams dish out. It helps to know where it can be put to good use. It is delicate enough that it requires smooth flow and really shines on calm water. If there is much turbulence it’s best to go up in dry fly size (often beyond Baetis size) for the buoyancy, so you can add weight to the dropper.

Still more turbulence? In my mind the dry/dropper deal hits diminished returns quickly. “Dead-drift” below the surface is not accomplished (in anything other than laminar flow) the same way it is with a dry fly, because strike detection is destroyed when you introduce the slack you need to get a natural drift with a dry. Instead, a nymph must be lead (pulled), as you mention, one way or another, even with an indicator (except possibly on really laminar flow, both horizontally across the lane and vertically, which is rarely offered by streams, (but more apt to be found in the more stable lowland rivers). Such spots DO exist on smaller waters, and recognizing laminar flow is key to catching. Sometimes they are rather large and long –“soft spots” I call them (coined by Tom Rosenbauer) - but most are discrete. Trout know them, as this is where they drift feed.

It is possible to attack the more turbulent (and deeper) spots by going up in shot weight, which then requires more buoyancy in the indicator, and a larger outfit to handle it. The difference does not appear to be linear, but exponential (to some unknown factor). I can indicator fish pretty “heavy” water when steelheading, but by then I’ve gone up to a 9wt outfit! For trout fishing, well before I need to break out the 9wt, I’ve dropped the indicators altogether, and fish heavier waters by feel.

Martinlf on Feb 2, 2012February 2nd, 2012, 12:03 pm EST

Paul, I've copied and pasted your directions into my "technique" folder. Thank you for the detail. Are you keeping your tungsten putty in an inside pocket or have you found a brand that doesn't harden too much in the cold? I typically use shot in the winter and colder spring days because the Loon putty I have gets hard as a rock, and I never remember to put it close enough to my body to keep it pliable. I did Google Parafilm, and am curious. Typically, I like to try different materials, and I'll be looking for a way to get my hands on a bit of it. Perhaps some of my colleagues in the sciences have some in their labs. I'm assuming you don't use hemostats on it.

Also very interesting to read about your use of this method on the D. Last year I worked very hard one day to catch several fish feeding on olives. It was, for me, a pretty good day, but I'll bet using this method would have given me more hookups. I have gone dry/dropper there several times on fish I could not get to take a solo dry, and it has worked--but did not occur to me, and I'm sometimes very stubborn when I think a fish should just cooperate and eat what I'm throwing.

Have you ever used Coq de Leon tails/legs? I just ordered a saddle for tailing primarily, and am going to give them a try, I think.

Also very interesting to read about your use of this method on the D. Last year I worked very hard one day to catch several fish feeding on olives. It was, for me, a pretty good day, but I'll bet using this method would have given me more hookups. I have gone dry/dropper there several times on fish I could not get to take a solo dry, and it has worked--but did not occur to me, and I'm sometimes very stubborn when I think a fish should just cooperate and eat what I'm throwing.

Have you ever used Coq de Leon tails/legs? I just ordered a saddle for tailing primarily, and am going to give them a try, I think.

"He spread them a yard and a half. 'And every one that got away is this big.'"

--Fred Chappell

--Fred Chappell

PaulRoberts on Feb 2, 2012February 2nd, 2012, 1:18 pm EST

I've used Loon, Right now I've got something called "Mud...something or other". They all get hard in the cold. I have had that issue, and gone to shot. But I can usually chip off and warm a small piece well enough -I have pretty good circulation in my hands. Friction can warm it too. Putty dries as it ages too, making it that much worse.

No hemostats on Parafilm flies. They get torn up by teeth too, but can also be re-shaped somewhat when warmed. I've caught a bunch of fish on single flies. Durability is not a huge issue.

Adding droppers is somewhat of a pain, but can be worthwhile. And sometimes we just want to fish the way we want to fish -fish be damned.

I have not used CdL. If the barbs are stiff enough I'd prefer it over fibettes, simply bc it's not a synthetic. Also, Fibettes (and paint brush bristles -what I use) being nylon absorb water after a while.

No hemostats on Parafilm flies. They get torn up by teeth too, but can also be re-shaped somewhat when warmed. I've caught a bunch of fish on single flies. Durability is not a huge issue.

Adding droppers is somewhat of a pain, but can be worthwhile. And sometimes we just want to fish the way we want to fish -fish be damned.

I have not used CdL. If the barbs are stiff enough I'd prefer it over fibettes, simply bc it's not a synthetic. Also, Fibettes (and paint brush bristles -what I use) being nylon absorb water after a while.

Martinlf on Feb 2, 2012February 2nd, 2012, 2:39 pm EST

"He spread them a yard and a half. 'And every one that got away is this big.'"

--Fred Chappell

--Fred Chappell

Martinlf on Feb 2, 2012February 2nd, 2012, 2:41 pm EST

I'll let you know more abut the CdL when I get the saddle, but it's my understanding that they are pretty stiff, and durable. I've lost mallard flank tails a time or two and that's one reason I'm looking to use the CdL fibers.

"He spread them a yard and a half. 'And every one that got away is this big.'"

--Fred Chappell

--Fred Chappell

Entoman on Feb 2, 2012February 2nd, 2012, 3:01 pm EST

There are a few patterns that I tend to lean towards during baetid season when wanting to fish attractors deep, but those are for another discussion. For shallow imitative nymphs used while fish are active at the surface, I've pretty much simplified my choices to just two patterns. When a little motion is desirable, IMO the original Sawyer PT can't be beat (though I've tweaked it quite a bit). I've found them wanting though for dead drift presentations. My favorite nymph pattern for that is in the more realistic Edwards style. The splayed legs and tails and glistening bulge of the emergent between the dark wingpads are real triggers. It doesn't hurt that the overall look is pretty suggestive as well.

Below is my imitation for Baetis tricaudatus. It has been my go-to for several years, and really hammered them this past Fall.

#18 Little Olive Quill Nymph

Baetis tricaudatus Nymph

#18 Little Olive Quill Nymph

Fly orientation & proper depth is an interesting topic and more important than many realize. I've found there are times a heavy nymph off the back of a dry fly fishes too deep (especially on spring creeks and calmer sections of large freestones). The trout often want them pretty close to the surface when you see them swirling and they also want them upright and horizontal as possible. Proper nymph technique is no different than good dry fly technique in this regard. What dry fly fisher would settle for a fly that floats upside down or (emergers aside) tail down? Nymphs should be tied unweighted on nymph hooks or even dry fly hooks for really gentle currents. Most anglers depend on the fact that competent designers are looking out for them in this regard, but it is a sad fact that most commercial offerings often fish upside down on the drift.

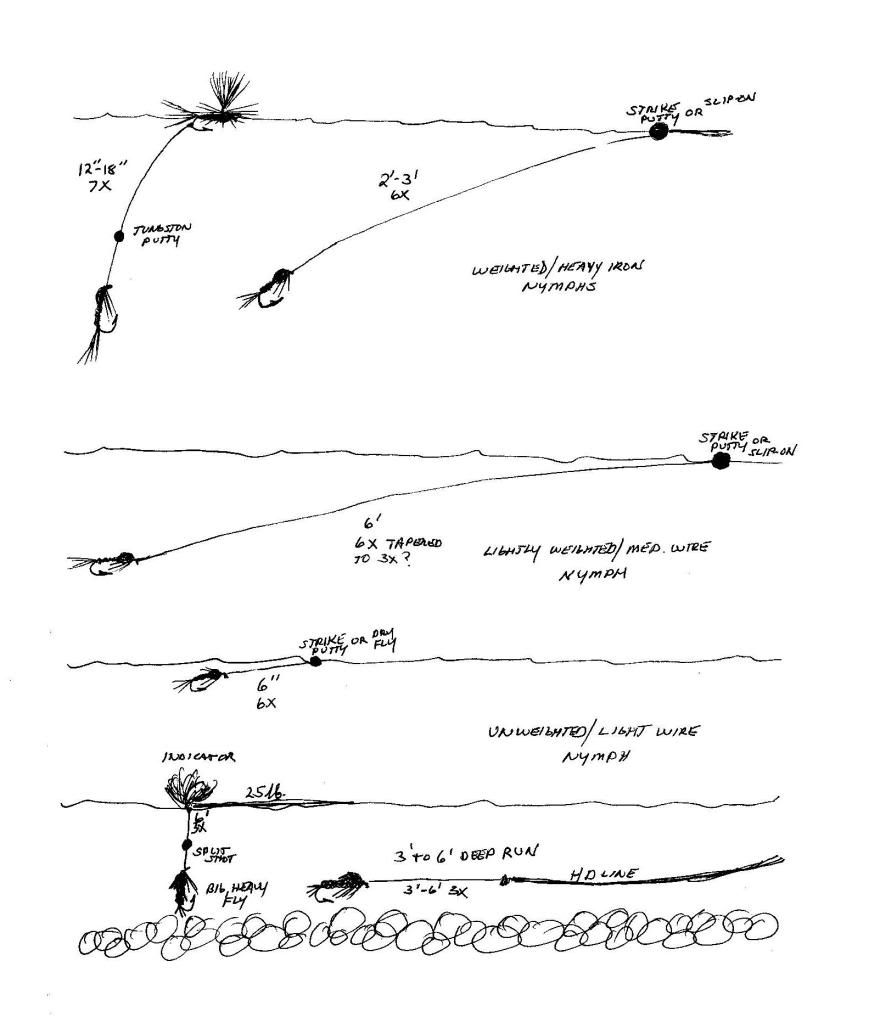

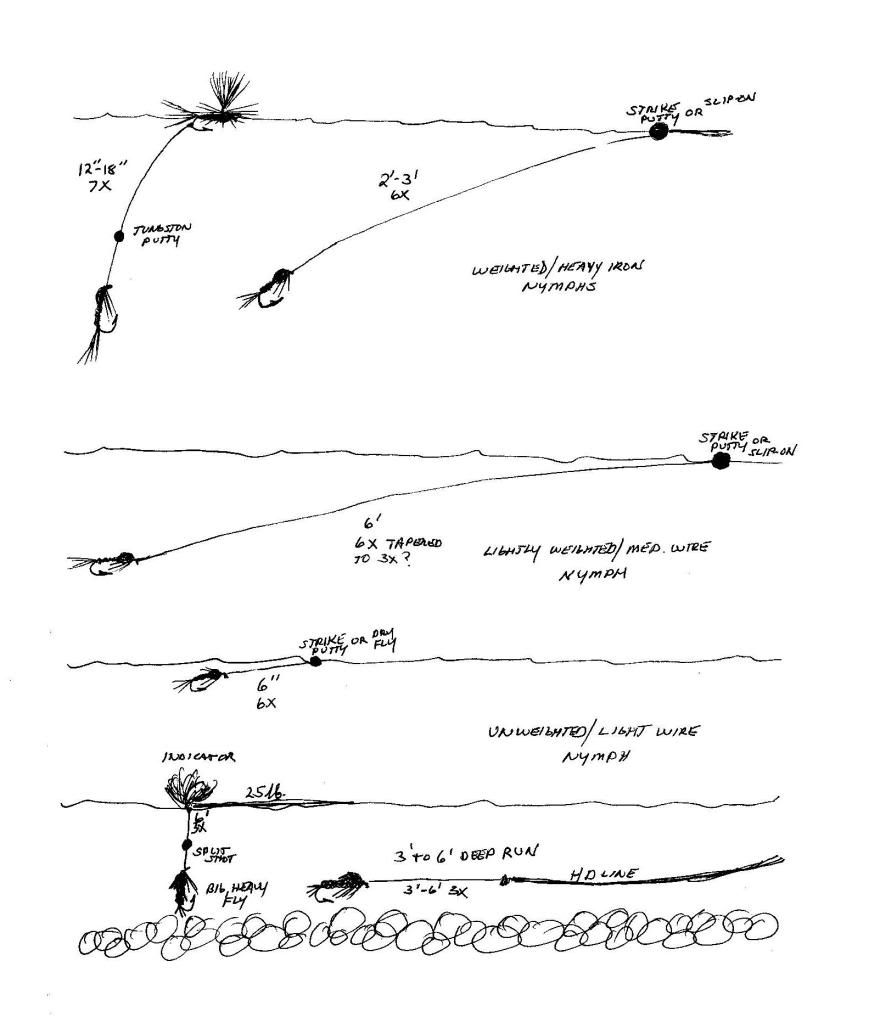

For those conditions, I prefer to fish them extremely shallow with a tiny bead of strike putty (to keep the fly up, not as an indicator) about six inches up from the fly. Six inches of tippet off the back of a dry fly is just too short for fighting fish with such gossamer and if the dropper is much longer the fly sinks too deep. Not much is lost anyway, as smart fish usually pick up on the micro-drag or aren't much interested in a dry that much bigger. I also use 6X (or even 5X) as it helps in two ways, first by keeping the fly from sinking deeper and more out of the horizontal (being a little more resistant to hinging at the indicator) and perhaps more importantly allows me to have a chance with the 20" plus fish that work this hatch on some of my home rivers since the springy 48" tippet is utilized full length. Below is a sketch I made today that looks at a few popular methods to give an idea about orientation.

To complete the picture for this critter in the same post, below is a photo of him in the dun stage and below that is a picture of the imitation I prefer for his girlfriend. BTW - The flies in this post came from my fly trap and are not fresh from my box. They each caught quite a few fish. Though delicate, they are very durable.

Baetis tricaudatus male dun

Sorry for the bent hackles (they also slipped up the post a bit), fish will do what they do.:) An interesting note on the photo if you enlarge it... That shiny spot dorsally on the head isn't cement, it's a fish scale. It must have gotten trapped under the loop of the turle knot after retying it on (something good to do after landing a couple of good fish). I didn't notice it until looking at the photo. How do I know? This fly has no head; the hackle is whipped to the post as the last step.

#18 Little Olive Quill Paradun

Below is my imitation for Baetis tricaudatus. It has been my go-to for several years, and really hammered them this past Fall.

#18 Little Olive Quill Nymph

Baetis tricaudatus Nymph

#18 Little Olive Quill Nymph

Fly orientation & proper depth is an interesting topic and more important than many realize. I've found there are times a heavy nymph off the back of a dry fly fishes too deep (especially on spring creeks and calmer sections of large freestones). The trout often want them pretty close to the surface when you see them swirling and they also want them upright and horizontal as possible. Proper nymph technique is no different than good dry fly technique in this regard. What dry fly fisher would settle for a fly that floats upside down or (emergers aside) tail down? Nymphs should be tied unweighted on nymph hooks or even dry fly hooks for really gentle currents. Most anglers depend on the fact that competent designers are looking out for them in this regard, but it is a sad fact that most commercial offerings often fish upside down on the drift.

For those conditions, I prefer to fish them extremely shallow with a tiny bead of strike putty (to keep the fly up, not as an indicator) about six inches up from the fly. Six inches of tippet off the back of a dry fly is just too short for fighting fish with such gossamer and if the dropper is much longer the fly sinks too deep. Not much is lost anyway, as smart fish usually pick up on the micro-drag or aren't much interested in a dry that much bigger. I also use 6X (or even 5X) as it helps in two ways, first by keeping the fly from sinking deeper and more out of the horizontal (being a little more resistant to hinging at the indicator) and perhaps more importantly allows me to have a chance with the 20" plus fish that work this hatch on some of my home rivers since the springy 48" tippet is utilized full length. Below is a sketch I made today that looks at a few popular methods to give an idea about orientation.

To complete the picture for this critter in the same post, below is a photo of him in the dun stage and below that is a picture of the imitation I prefer for his girlfriend. BTW - The flies in this post came from my fly trap and are not fresh from my box. They each caught quite a few fish. Though delicate, they are very durable.

Baetis tricaudatus male dun

Sorry for the bent hackles (they also slipped up the post a bit), fish will do what they do.:) An interesting note on the photo if you enlarge it... That shiny spot dorsally on the head isn't cement, it's a fish scale. It must have gotten trapped under the loop of the turle knot after retying it on (something good to do after landing a couple of good fish). I didn't notice it until looking at the photo. How do I know? This fly has no head; the hackle is whipped to the post as the last step.

#18 Little Olive Quill Paradun

"It's not that I find fishing so important, it's just that I find all other endeavors of Man equally unimportant... And not nearly as much fun!" Robert Traver, Anatomy of a Fisherman

PaulRoberts on Feb 2, 2012February 2nd, 2012, 4:04 pm EST

Great post Kurt. Nice flies, illustrations, and descriptions. This is turning into a nice thread. Anyone else want to chip in?

Yeah, there's more than one way to skin a cat, and lotsa variables. Also, interesting, I can see in your rigging that you are probably fishing much slower (probably bigger) waters than I presently do. Most of my Baetid fishing is done on smaller streams now, where lanes can be pretty short, and not all that stately. Closest I get to "stately" flow are the tailouts, and a few large flat pools tucked away here and there.

Louis, yeah, mallard flank is pretty but not terribly stiff, or durable. Cemented maybe?

I re-edited my post above to clarify fishing the combination on my waters.

Yeah, there's more than one way to skin a cat, and lotsa variables. Also, interesting, I can see in your rigging that you are probably fishing much slower (probably bigger) waters than I presently do. Most of my Baetid fishing is done on smaller streams now, where lanes can be pretty short, and not all that stately. Closest I get to "stately" flow are the tailouts, and a few large flat pools tucked away here and there.

Louis, yeah, mallard flank is pretty but not terribly stiff, or durable. Cemented maybe?

I re-edited my post above to clarify fishing the combination on my waters.

Entoman on Feb 2, 2012February 2nd, 2012, 5:09 pm EST

Paul -

Ah... Good point. Less anyone be misled, the methods presented and discussed here are complimentary, not contradictory, and they all have their place. Proper technique selection and fly choice are greatly dependent on water type, insect activity, and the fish's response to them. There are circumstances where certain techniques work better than others and also times when particular ones are dead wrong - and is that a lesson I've learned the hard way many times over the years!:)

Ah... Good point. Less anyone be misled, the methods presented and discussed here are complimentary, not contradictory, and they all have their place. Proper technique selection and fly choice are greatly dependent on water type, insect activity, and the fish's response to them. There are circumstances where certain techniques work better than others and also times when particular ones are dead wrong - and is that a lesson I've learned the hard way many times over the years!:)

"It's not that I find fishing so important, it's just that I find all other endeavors of Man equally unimportant... And not nearly as much fun!" Robert Traver, Anatomy of a Fisherman

Martinlf on Feb 3, 2012February 3rd, 2012, 11:57 am EST

Here's another bit for the thread. My favorite nymph-in-the-film olive fly is a little Klinkhamer style parachute. This can also be tied thorax-style with cut wings, though that's getting further from the nymph. I've tied these with little loops of 3X (or 4X, can't remember for sure) Maxima mono at the tails to drop nymphs from, but haven't tried gel spun--yet. I also like RS2's with a CDC wing and shuck.

"He spread them a yard and a half. 'And every one that got away is this big.'"

--Fred Chappell

--Fred Chappell

Entoman on Feb 3, 2012February 3rd, 2012, 5:33 pm EST

Here's another bit for the thread. My favorite nymph-in-the-film olive fly is a little Klinkhamer style parachute.

Me too Louis, though I agree it is technically an emerger. In case you missed it, this linked thread has a good discussion about the origin of emergers towards the bottom of page 2.

http://www.troutnut.com/topic/2145/2/comparadun-question

"It's not that I find fishing so important, it's just that I find all other endeavors of Man equally unimportant... And not nearly as much fun!" Robert Traver, Anatomy of a Fisherman

GldstrmSam on Feb 3, 2012February 3rd, 2012, 6:32 pm EST

Entoman, Thanks for that diagram on fishing the nymph. That answered a question of mine before I had a chance to ask it.

Sam

Sam

There is no greater fan of fly fishing than the worm. ~Patrick F. McManus

Martinlf on Feb 4, 2012February 4th, 2012, 5:55 am EST

Kurt, I believe had missed that thread. At times I get very busy and disappear for a while. Thanks!

"He spread them a yard and a half. 'And every one that got away is this big.'"

--Fred Chappell

--Fred Chappell

Oldredbarn on Feb 4, 2012February 4th, 2012, 7:08 am EST

Louis,

I'm rather fond of the "Klinki" myself for Baetis...We have disscussed it elsewhere here somewhere. My version is next to impossible to see on the water, except in a few light conditions...I use a natural colored goose biot for the abdomen...Dark dun Hi-Vis for post and dark dun for the hackle...I dub a thorax of a mix of beaver that's dark brown with olive highlights...Thankfully the trout have better vision than I do...

The Klinkhammer was actually a caddis emerger originally but seems to work here as well...At the time that the early Baetis are about we can also have P adoptiva and some of the smaller darker early caddis (Brachycentrus sp)...So, who really knows exactly what's going on other than it must appear close enough to the feeding fish.

Nice flies there fellas...I have a loop-winged emerger I use on scud hooks and it can work really well when it actually sinks a bit...Thanks for the discussion on tactics. Depending on the species an emergence can really get the fish going and I think we all know, that for these bugs, it's like running a gauntlet :). Having a nice imitation that functions well in that "killing zone" will ultimately catch you fish.

Spence

I'm rather fond of the "Klinki" myself for Baetis...We have disscussed it elsewhere here somewhere. My version is next to impossible to see on the water, except in a few light conditions...I use a natural colored goose biot for the abdomen...Dark dun Hi-Vis for post and dark dun for the hackle...I dub a thorax of a mix of beaver that's dark brown with olive highlights...Thankfully the trout have better vision than I do...

The Klinkhammer was actually a caddis emerger originally but seems to work here as well...At the time that the early Baetis are about we can also have P adoptiva and some of the smaller darker early caddis (Brachycentrus sp)...So, who really knows exactly what's going on other than it must appear close enough to the feeding fish.

Nice flies there fellas...I have a loop-winged emerger I use on scud hooks and it can work really well when it actually sinks a bit...Thanks for the discussion on tactics. Depending on the species an emergence can really get the fish going and I think we all know, that for these bugs, it's like running a gauntlet :). Having a nice imitation that functions well in that "killing zone" will ultimately catch you fish.

Spence

"Even when my best efforts fail it's a satisfying challenge, and that, after all, is the essence of fly fishing." -Chauncy Lively

"Envy not the man who lives beside the river, but the man the river flows through." Joseph T Heywood

"Envy not the man who lives beside the river, but the man the river flows through." Joseph T Heywood

PaulRoberts on Feb 4, 2012February 4th, 2012, 8:25 am EST

Yes, the Paraleps can come about the same time as the tricaudatus, but don't start as early I think. And I think they were a mid-morning deal where tricaudatus has more of an afternoon peak. (Here in the rockies we're not supoosed to don't have the early P adoptiva, although last spring I found a single youngish nymph that my key would only take it to adoptiva -by gills if I remember right. Wish I'd pickled it and had it properly ID'd.

Anyway, back east I found the Paraleps emerged from slower currents and siltier substrates -often along stream edges. Whereas tricaudatus spilled out of the riffles. They could mix of course in certain places, but one could find one predominant if you wanted to (and I did bc I wanted to know each better) by focusing on key habitat.

Anyway, back east I found the Paraleps emerged from slower currents and siltier substrates -often along stream edges. Whereas tricaudatus spilled out of the riffles. They could mix of course in certain places, but one could find one predominant if you wanted to (and I did bc I wanted to know each better) by focusing on key habitat.

Martinlf on Feb 4, 2012February 4th, 2012, 12:14 pm EST

Spence, tie a few klinks with white or brightlly colored posts, if your aesthetics will allow. I've found most, if not all, fish don't seem to mind, and in the grey glare of a cloudy spring day it can help a great deal. My current favorite colored posts are hot pink and an intense red/orange from some stuff (antron?) of unknown origin I've had forever, though I also use grey/dun hi-vis and poly yarn for about half my ties. The Klink is my standard mayfly pattern, the one I try first with most hatches. If I want gills, I'll use marabou instead of the biot. I tie a similar caddis, but all dubbing and buggier, with a little partridge wing and some beard hackle.

"He spread them a yard and a half. 'And every one that got away is this big.'"

--Fred Chappell

--Fred Chappell

Entoman on Feb 4, 2012February 4th, 2012, 12:25 pm EST

My current favorite colored posts are hot pink and an intense red/orange

Yes! Especially on bigger water capable of foam lines and glare. Throw in a thousand bugs and casts longer than 30ft and you can forget about seeing your fly with a dun or white post. I like fl. pink with the olives and fl. orange with the sulfurs. In the circumstances mentioned, I haven't noticed the fish being put off and the whole thing sure works better when you can see your fly!:) Same thing goes for parachutes as well. For that matter, even as a topping for elkhairs or as little humpy/wulff wings.

"It's not that I find fishing so important, it's just that I find all other endeavors of Man equally unimportant... And not nearly as much fun!" Robert Traver, Anatomy of a Fisherman

Gutcutter on Feb 5, 2012February 5th, 2012, 7:02 am EST

It may sound strange, but I have found that a black post (or wing) shows up really well, especially when there is some glare on the water.

The first olives that we (Bruce, Louis, Shawn and I) see here in Central PA, are also (I believe) tricaudatus and are 18's (Tiemco).

For the olives, I, too, can attest that a "two fly rig" works well. I like what I see in those drawings above.

The "dropper" that I'm fond of is a simple, glass bead headed, golden olive nymph. Soaked with stream water well (or with a bit of Xink) and attached by ten to fourteen inches of 5x, it gets down about one or two inches below the surface film and is deadly on those smutting risers.

My observation (for what it's worth):

Most years, these Small Olives begin to hatch a few weeks behind the Little Black Stones, about two weeks before the QG and Grannom and almost a full month before our P adoptiva and E subvaria do.

The first olives that we (Bruce, Louis, Shawn and I) see here in Central PA, are also (I believe) tricaudatus and are 18's (Tiemco).

For the olives, I, too, can attest that a "two fly rig" works well. I like what I see in those drawings above.

The "dropper" that I'm fond of is a simple, glass bead headed, golden olive nymph. Soaked with stream water well (or with a bit of Xink) and attached by ten to fourteen inches of 5x, it gets down about one or two inches below the surface film and is deadly on those smutting risers.

My observation (for what it's worth):

Most years, these Small Olives begin to hatch a few weeks behind the Little Black Stones, about two weeks before the QG and Grannom and almost a full month before our P adoptiva and E subvaria do.

All men who fish may in turn be divided into two parts: those who fish for trout and those who don't. Trout fishermen are a race apart: they are a dedicated crew- indolent, improvident, and quietly mad.

-Robert Traver, Trout Madness

-Robert Traver, Trout Madness

Quick Reply

Related Discussions

Topic

Replies

Last Reply

5

Jun 14, 2008

by Wiflyfisher

by Wiflyfisher

1

Mar 9, 2012

by Wiflyfisher

by Wiflyfisher

1

Jul 11, 2008

by Taxon

by Taxon