Blue-winged Olives

Baetis

Tiny Baetis mayflies are perhaps the most commonly encountered and imitated by anglers on all American trout streams due to their great abundance, widespread distribution, and trout-friendly emergence habits.

Featured on the forum

Some characteristics from the microscope images for the tentative species id: The postero-lateral projections are found only on segment 9, not segment 8. Based on the key in Jacobus et al. (2014), it appears to key to Neoleptophlebia adoptiva or Neoleptophlebia heteronea, same as this specimen with pretty different abdominal markings. However, distinguishing between those calls for comparing the lengths of the second and third segment of the labial palp, and this one (like the other one) only seems to have two segments. So I'm stuck on them both. It's likely that the fact that they're immature nymphs stymies identification in some important way.

Troutnut is a project started in 2003 by salmonid ecologist Jason "Troutnut" Neuswanger to help anglers and

fly tyers unabashedly embrace the entomological side of the sport. Learn more about Troutnut or

support the project for an enhanced experience here.

Adirman on Jun 2, 2011June 2nd, 2011, 2:37 pm EDT

Interesting discussion on another fly fishing forum I'm a member of that I wanted to bring here to get some thoughts. Can you truly tell the difference betwen stocked and wild trout, especially if the adipose fin is NOT clipped on the stocker? Opinions seem to vary. Many guys say that stocked trout are less colorful, less muscular, don't fight as hard etc. My opinion is that this may be true for 1st season stockers but after the 2nd and especially the4 3rd season, those stockers become wild trout, not only in behavior, but also in appearance!! These stockers would be virtually indistinguishable in appearance I would think as compared to a wild fish born and raised in its home river/stream. What do you think?

Thanks,

Adirman

Thanks,

Adirman

Softhackle on Jun 2, 2011June 2nd, 2011, 5:45 pm EDT

Adirman,

Sometimes, I find it difficult to tell, while other times not. I've read that they have developed a new trout food for the hatcheries which improves the coloration of the stockies. Therefore I would not judge by color.

A telltale is usually ragged pectoral fins. They get this way from sitting in the cement holding tanks and rubbing on the bottom. I was told while they may recover some from this, the fins never really become perfectly reformed. I've seen these fins worn pretty badly on the two year old fish DEC now stocks in many streams in NY.

Mark

Sometimes, I find it difficult to tell, while other times not. I've read that they have developed a new trout food for the hatcheries which improves the coloration of the stockies. Therefore I would not judge by color.

A telltale is usually ragged pectoral fins. They get this way from sitting in the cement holding tanks and rubbing on the bottom. I was told while they may recover some from this, the fins never really become perfectly reformed. I've seen these fins worn pretty badly on the two year old fish DEC now stocks in many streams in NY.

Mark

"I have the highest respect for the skilled wet-fly fisherman, as he has mastered an art of very great difficulty." Edward R. Hewitt

Flymphs, Soft-hackles and Spiders: http://www.troutnut.com/libstudio/FS&S/index.html

Flymphs, Soft-hackles and Spiders: http://www.troutnut.com/libstudio/FS&S/index.html

Adirman on Jun 3, 2011June 3rd, 2011, 11:50 am EDT

Softhackle;

Thank you sir, that was the BEST reply on 2 forums I've received yet!! So the ragged fins look, although it may diminish w/ time, you think would be the best way to differentiate former stockers from wild trout? What about the notion of difference in strength/fighting ability when caught that some guys talk about? I think that's mostly hogwash, what do you think??

Thanks,

Adirman

Thank you sir, that was the BEST reply on 2 forums I've received yet!! So the ragged fins look, although it may diminish w/ time, you think would be the best way to differentiate former stockers from wild trout? What about the notion of difference in strength/fighting ability when caught that some guys talk about? I think that's mostly hogwash, what do you think??

Thanks,

Adirman

Softhackle on Jun 3, 2011June 3rd, 2011, 3:34 pm EDT

Adirman,

Let's go back to those two-year old fish for a minute. They've been under human control for two years. They've grown accustomed to man, and I find that when released they are initially easier to catch and don't have much fight. After a bit of exposure in nature, (if they stay uncaught for a while) they can get pretty feisty. So are the younger stocked fish, I think, because they have not been exposed to man as long. I've had many older holdover trout fight as well as the stream-born trout I've taken.

So, initially, stockies might be a push over depending upon how long they've been captive, but give them some free time in the water and they can become just as feisty and wary as any stream-born trout, I feel.

Mark

Let's go back to those two-year old fish for a minute. They've been under human control for two years. They've grown accustomed to man, and I find that when released they are initially easier to catch and don't have much fight. After a bit of exposure in nature, (if they stay uncaught for a while) they can get pretty feisty. So are the younger stocked fish, I think, because they have not been exposed to man as long. I've had many older holdover trout fight as well as the stream-born trout I've taken.

So, initially, stockies might be a push over depending upon how long they've been captive, but give them some free time in the water and they can become just as feisty and wary as any stream-born trout, I feel.

Mark

"I have the highest respect for the skilled wet-fly fisherman, as he has mastered an art of very great difficulty." Edward R. Hewitt

Flymphs, Soft-hackles and Spiders: http://www.troutnut.com/libstudio/FS&S/index.html

Flymphs, Soft-hackles and Spiders: http://www.troutnut.com/libstudio/FS&S/index.html

Jmd123 on Jun 3, 2011June 3rd, 2011, 4:45 pm EDT

About 20 years ago I fished a stream in south-central Michigan that held lots of nice brown trout but wasn't good enough habitat for spawning (too silty?). The stockers went in well under legal size (8" in those days, not sure what it is there now but might be 10") and by the time they were a foot long, they had bright lemon-yellow bellies and red spots on their sides, fought very well, and hammered dry flies with abandon. I never paid any attention to their pectoral fins, but it was hard to believe they weren't born there. I haven't been back since but it's still mapped as trout waters...

Some time ago there was an article in one of the fly fishing magazines about research into artificial trout diets, discussing the lack of copper as a trace element which is naturally present in insect "blood" (hemolymph -it's light blue in color from the copper). When trace amounts of copper were added to the artificial diet, colors brightened and it also improved fin development (not that it would help the rubbing problem but it did help the other fins grow fuller). I mentioned it on here a few years ago but I don't remember the magazine or date of the article. You could probably Google it though with key words like "trout" and "artificial diet".

Jonathon

Some time ago there was an article in one of the fly fishing magazines about research into artificial trout diets, discussing the lack of copper as a trace element which is naturally present in insect "blood" (hemolymph -it's light blue in color from the copper). When trace amounts of copper were added to the artificial diet, colors brightened and it also improved fin development (not that it would help the rubbing problem but it did help the other fins grow fuller). I mentioned it on here a few years ago but I don't remember the magazine or date of the article. You could probably Google it though with key words like "trout" and "artificial diet".

Jonathon

No matter how big the one you just caught is, there's always a bigger one out there somewhere...

Softhackle on Jun 3, 2011June 3rd, 2011, 6:41 pm EDT

"I have the highest respect for the skilled wet-fly fisherman, as he has mastered an art of very great difficulty." Edward R. Hewitt

Flymphs, Soft-hackles and Spiders: http://www.troutnut.com/libstudio/FS&S/index.html

Flymphs, Soft-hackles and Spiders: http://www.troutnut.com/libstudio/FS&S/index.html

Jmd123 on Jun 3, 2011June 3rd, 2011, 7:08 pm EDT

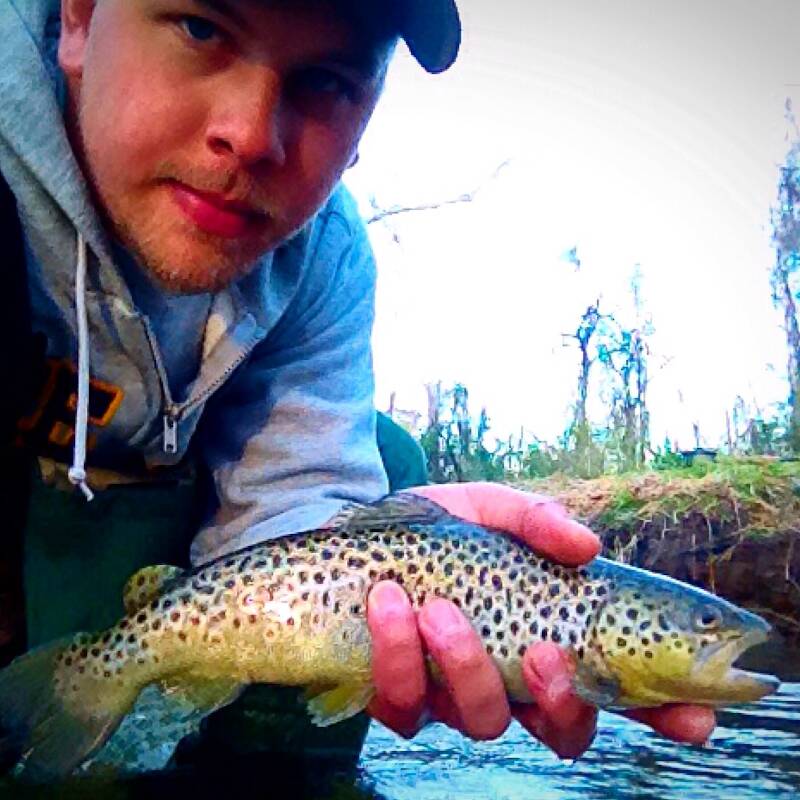

I don't think I'd have a problem enjoying that fish! Looks like your friend didn't either...

Jonathon

Jonathon

No matter how big the one you just caught is, there's always a bigger one out there somewhere...

PaulRoberts on Jun 4, 2011June 4th, 2011, 11:10 am EDT

Experience and thoughts on stocked vs wild trout…

There are a number of things, obvious and/or contextual. I’d add images but most are not digitized. Will try to describe…

Fin Distortion:

Mark mentions warped fins, and that is the most recognizable, longest lasting, feature of stocked trout –at least those that were in hatchery conditions beyond the fingerling stage. Most trout, esp for put-n-take purposes, and in streams, are stocked as yearlings –long enough for the crowded conditions in hatchery raceways and pools to result in warped fin rays. The leading edge of the dorsal fin shows it most, the pectorals next, and occasionally the pelvics. When trout are stocked as fry or fingerlings (usually large volume stocking of lakes) the fins may not show much warping. Streambred fish tend to have a straight (unwarped) leading edge of the dorsal fin. If your fish has even a slight dorsal warp, it’s a prime candidate for factory origin.

Pecs and pelvics are also the targets for fin-clipping, where that’s done. Fin clipping is often done on fingerlings released into lakes. As adults such fish would be difficult to recognize as stockies otherwise. Fin clipping is not easy to do –somewhat of a skill you need to get used to. You have to clip right at the joint at the pelvic girdle –too shallow and the fin will regenerate (although distorted), too deep and the little fish is at risk of infection.

Tails are not as good an indicator of origin bc they can commonly become distorted naturally, from either:

-Redd digging when spawning showing up on at the bottom edge, and lower lobe of the caudal fin. These heal after a month or so depending on fish health.

-Habitual holding at foraging or hiding sites from repetitive abrasion against substrate. These are more common on browns and brookies bc they are more cover oriented, and also commonly use the calm water just ahead of rocks, deadwood, and tailouts as key drift-feeding sites (I call these spots 'cushions'). This abrasion shows up usually on the lower lobe of the caudal fin and are still inflamed during summer (compared to spawning abrasions).

Truly large browns from small streams often have abraded tails, often the top lobe of the caudal fin, from stuffing themselves under cover during daylight hours, often undercuts and logjams that result in the upper lobe being abraded. I‘ve also seen this type of tail distortion in larger resident (non-migratory) Finger Lakes rainbows –a certain small segment of those populations remain stream resident and use wood cover.

Coloration:

As Mark’s image of a super-nice holdover brown shows, coloration isn’t always a good determinate. But, in recently stocked trout coloration it is. And in many holdovers too, bc, in the streams I’ve fished, trout do not recover colors well or maybe it just takes more time (years). Small stream fish tend to have shorter lives than river or lake fish. Possibly, the ability to adapt to stream life –become effective residents –enters in.

Trout are almost chameleon-like in their ability to adjust color, associated with water and sky conditions, life history periods, and behavioral requirements. Their colors are a combination of camouflage and communication requirements.

Recently stocked trout tend to be duller in coloration. In hatchery raceways they are so bc of the concrete lined raceways. But I’ve seen some fairly pretty browns in hatchery “finishing ponds” that offer more natural backdrops. Stocked trout seem to hold this dull gunmetal (in brookies), olive in browns, for at least a year, often showing up the same way, but with stronger spotting, as holdovers. I’ve caught some pretty ones, like the one Mark shows, but these are rarer, possibly older, fish. The following tries to account for their existence in spite of the challenges stockies face:

Behavior/Life History “Strategy”:

The fact is, most stocked trout die, esp when dumped into streams, since they are not accustomed to (downright ill-equipped for) the energetic rigors of drift feeding. Many are stocked too large for smaller streams to support, at least in such numbers. One thing they do know is that they are not getting enough food so they tend to drop downstream, further and further, until they get into too warm water down the watershed as summer comes on. I’ve seen such fish (by direct observation, hook-n-line fishing, and electro-fishing) in 80degree water and these fish tend to be emaciated. An interesting study compared hatchery and long-established streambred (Catskill) browns “stocked” into a trout stream. The stockies dropped downstream (into more food but potential heat trouble), and the wild fish moved upstream –presumably toward cooler headwaters as many small stream trout that know their schtick do come summer heat up.

It appears that a very few “drop-outs” survive. If they remain in “trout water” they become “holdovers” and live by drift feeding and/or aggressive pursuit feeding of larger prey items. Pursuit feeders, btw, have the opportunity to outgrow strict drift feeders. Hatchery trout, raised in crowded raceways, and fed tossed pelleted food, develop aggressive feeding behavior, and those that are the best at it, grow fastest. And that’s just what a hatchery manager wants, to meet stocking size range requiremsnts. Some drop-outs may find pockets of cool water down the watershed, where there is often larger habitat and more food, and such fish can grow LARGE. Some wild fish find their way to these places too, either by having the penchant to migrate, swept from flooding, or possibly as descendants of successful holdovers.

This “penchant for migrating” is interesting. Our brown trout are all from Europe and being indigenous salmonids several strains/morphs/flavors developed -often within populations- and these were introduced and mixed in hatchery stocks. Some brown trout, in streams attached to lakes or the ocean, have a segment of their populations that “go migratory”. Studies have shown that they can come from the same redd as non-migratory individuals. What sends them to the sea appears to be either a genetic switch that turns on, environmental conditions, or rapid growth that results in those individuals outstripping their food supply. Sounds a lot like hatchery trout grown fast and large (and aggressive) in a hatchery to meet stocking size quotas, and then dumped into a wild stream where the rules are completely different. Thus, when I catch outsized trout, notably browns, from smaller streams, they are apt to be holdovers (with warped dorsals) for, I believe, the above reasons.

There are a number of things, obvious and/or contextual. I’d add images but most are not digitized. Will try to describe…

Fin Distortion:

Mark mentions warped fins, and that is the most recognizable, longest lasting, feature of stocked trout –at least those that were in hatchery conditions beyond the fingerling stage. Most trout, esp for put-n-take purposes, and in streams, are stocked as yearlings –long enough for the crowded conditions in hatchery raceways and pools to result in warped fin rays. The leading edge of the dorsal fin shows it most, the pectorals next, and occasionally the pelvics. When trout are stocked as fry or fingerlings (usually large volume stocking of lakes) the fins may not show much warping. Streambred fish tend to have a straight (unwarped) leading edge of the dorsal fin. If your fish has even a slight dorsal warp, it’s a prime candidate for factory origin.

Pecs and pelvics are also the targets for fin-clipping, where that’s done. Fin clipping is often done on fingerlings released into lakes. As adults such fish would be difficult to recognize as stockies otherwise. Fin clipping is not easy to do –somewhat of a skill you need to get used to. You have to clip right at the joint at the pelvic girdle –too shallow and the fin will regenerate (although distorted), too deep and the little fish is at risk of infection.

Tails are not as good an indicator of origin bc they can commonly become distorted naturally, from either:

-Redd digging when spawning showing up on at the bottom edge, and lower lobe of the caudal fin. These heal after a month or so depending on fish health.

-Habitual holding at foraging or hiding sites from repetitive abrasion against substrate. These are more common on browns and brookies bc they are more cover oriented, and also commonly use the calm water just ahead of rocks, deadwood, and tailouts as key drift-feeding sites (I call these spots 'cushions'). This abrasion shows up usually on the lower lobe of the caudal fin and are still inflamed during summer (compared to spawning abrasions).

Truly large browns from small streams often have abraded tails, often the top lobe of the caudal fin, from stuffing themselves under cover during daylight hours, often undercuts and logjams that result in the upper lobe being abraded. I‘ve also seen this type of tail distortion in larger resident (non-migratory) Finger Lakes rainbows –a certain small segment of those populations remain stream resident and use wood cover.

Coloration:

As Mark’s image of a super-nice holdover brown shows, coloration isn’t always a good determinate. But, in recently stocked trout coloration it is. And in many holdovers too, bc, in the streams I’ve fished, trout do not recover colors well or maybe it just takes more time (years). Small stream fish tend to have shorter lives than river or lake fish. Possibly, the ability to adapt to stream life –become effective residents –enters in.

Trout are almost chameleon-like in their ability to adjust color, associated with water and sky conditions, life history periods, and behavioral requirements. Their colors are a combination of camouflage and communication requirements.

Recently stocked trout tend to be duller in coloration. In hatchery raceways they are so bc of the concrete lined raceways. But I’ve seen some fairly pretty browns in hatchery “finishing ponds” that offer more natural backdrops. Stocked trout seem to hold this dull gunmetal (in brookies), olive in browns, for at least a year, often showing up the same way, but with stronger spotting, as holdovers. I’ve caught some pretty ones, like the one Mark shows, but these are rarer, possibly older, fish. The following tries to account for their existence in spite of the challenges stockies face:

Behavior/Life History “Strategy”:

The fact is, most stocked trout die, esp when dumped into streams, since they are not accustomed to (downright ill-equipped for) the energetic rigors of drift feeding. Many are stocked too large for smaller streams to support, at least in such numbers. One thing they do know is that they are not getting enough food so they tend to drop downstream, further and further, until they get into too warm water down the watershed as summer comes on. I’ve seen such fish (by direct observation, hook-n-line fishing, and electro-fishing) in 80degree water and these fish tend to be emaciated. An interesting study compared hatchery and long-established streambred (Catskill) browns “stocked” into a trout stream. The stockies dropped downstream (into more food but potential heat trouble), and the wild fish moved upstream –presumably toward cooler headwaters as many small stream trout that know their schtick do come summer heat up.

It appears that a very few “drop-outs” survive. If they remain in “trout water” they become “holdovers” and live by drift feeding and/or aggressive pursuit feeding of larger prey items. Pursuit feeders, btw, have the opportunity to outgrow strict drift feeders. Hatchery trout, raised in crowded raceways, and fed tossed pelleted food, develop aggressive feeding behavior, and those that are the best at it, grow fastest. And that’s just what a hatchery manager wants, to meet stocking size range requiremsnts. Some drop-outs may find pockets of cool water down the watershed, where there is often larger habitat and more food, and such fish can grow LARGE. Some wild fish find their way to these places too, either by having the penchant to migrate, swept from flooding, or possibly as descendants of successful holdovers.

This “penchant for migrating” is interesting. Our brown trout are all from Europe and being indigenous salmonids several strains/morphs/flavors developed -often within populations- and these were introduced and mixed in hatchery stocks. Some brown trout, in streams attached to lakes or the ocean, have a segment of their populations that “go migratory”. Studies have shown that they can come from the same redd as non-migratory individuals. What sends them to the sea appears to be either a genetic switch that turns on, environmental conditions, or rapid growth that results in those individuals outstripping their food supply. Sounds a lot like hatchery trout grown fast and large (and aggressive) in a hatchery to meet stocking size quotas, and then dumped into a wild stream where the rules are completely different. Thus, when I catch outsized trout, notably browns, from smaller streams, they are apt to be holdovers (with warped dorsals) for, I believe, the above reasons.

Jmd123 on Jun 4, 2011June 4th, 2011, 1:24 pm EDT

Another stocked vs. wild story for ya, this one from Oregon, where I lived in '92-'93 (Coos Bay) and worked (South Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve - my first real field biology job!). My ex-wife and I went fishing in the MacKenzie River, upstream from Eugene, and were nailing fish on Elkhair Caddis, size 12 with a yellow body and grey wing. Most were stockers, and they looked nice enough and we were keeping them. But one fish came up with really nice bright colors and big flaring fins, and I knew right away. Wow, THIS one's a wild fish, a native redband rainbow, and back in the water it went...

BTW Paul, nice discussion, very informative!

Jonathon

BTW Paul, nice discussion, very informative!

Jonathon

No matter how big the one you just caught is, there's always a bigger one out there somewhere...

Adirman on Jun 4, 2011June 4th, 2011, 2:19 pm EDT

Paul;

Wow!! Now that's a post!! Nice pic of your friend holding that Brownie BTW!! Even if its a holdover like you say, probably pretty much behaved like a wild trout by the time it was caught and sure looked like it too (except for the pec fin, of course!!).

Wow!! Now that's a post!! Nice pic of your friend holding that Brownie BTW!! Even if its a holdover like you say, probably pretty much behaved like a wild trout by the time it was caught and sure looked like it too (except for the pec fin, of course!!).

PaulRoberts on Jun 4, 2011June 4th, 2011, 5:00 pm EDT

Paul;

Wow!! Now that's a post!! Nice pic of your friend holding that Brownie BTW!! Even if its a holdover like you say, probably pretty much behaved like a wild trout by the time it was caught and sure looked like it too (except for the pec fin, of course!!).

Thanks Adirman.

That beautiful fish was posted by Mark (Softhackle).

Motrout on Jun 6, 2011June 6th, 2011, 10:00 am EDT

I find this topic very interesting, and I don't have much to add.

But about the fight of a stocker trout vs. wild ones: I think that is a pretty unreliable way to tell. Of course a stream born fish of the same size is going to fight harder than a fish that was stocked last week, but once the fish has been in the water for anywhere from a few months to a few years, it can be pretty hard to tell the difference. One stretch of river that I fish a lot, the Blue Ribbon reaches of the Current in Missouri, is almost 100% stocked trout water. But almost without exception, the trout fight extremely hard, I'd say 100% as hard as their stream-born counterparts on nearby streams like the Eleven Point River. That's because the fish aren't fresh stockers. The stream is stocked once a year with browns, and also has rainbows that migrate downstream from a put and take area on the upper end of the river. With the exception of a few of the freshly stocked browns, by the time those fish are acclimated to that river, eating natural food and generally learning how to survive in the wild, they fight hard, and are just as feisty and almost as desirable to catch as stream born fish. Also many of the fish have beautiful, unique colorations that probably have something to do with the unique food base in the river. By looking at them (unless you look carefully at their fins as Softhackle mentioned) and fighting them, you'd be sure that most of the fish you were catching are wild. Only they aren't.

Now the twist on this river is that you do sometimes catch a wild rainbow trout. They are in there, just in very limited numbers. Usually the only way you can tell for sure is that the fish is smaller than the minimum stocking size (about 9 or 10 inches).

But about the fight of a stocker trout vs. wild ones: I think that is a pretty unreliable way to tell. Of course a stream born fish of the same size is going to fight harder than a fish that was stocked last week, but once the fish has been in the water for anywhere from a few months to a few years, it can be pretty hard to tell the difference. One stretch of river that I fish a lot, the Blue Ribbon reaches of the Current in Missouri, is almost 100% stocked trout water. But almost without exception, the trout fight extremely hard, I'd say 100% as hard as their stream-born counterparts on nearby streams like the Eleven Point River. That's because the fish aren't fresh stockers. The stream is stocked once a year with browns, and also has rainbows that migrate downstream from a put and take area on the upper end of the river. With the exception of a few of the freshly stocked browns, by the time those fish are acclimated to that river, eating natural food and generally learning how to survive in the wild, they fight hard, and are just as feisty and almost as desirable to catch as stream born fish. Also many of the fish have beautiful, unique colorations that probably have something to do with the unique food base in the river. By looking at them (unless you look carefully at their fins as Softhackle mentioned) and fighting them, you'd be sure that most of the fish you were catching are wild. Only they aren't.

Now the twist on this river is that you do sometimes catch a wild rainbow trout. They are in there, just in very limited numbers. Usually the only way you can tell for sure is that the fish is smaller than the minimum stocking size (about 9 or 10 inches).

"I don't know what fly fishing teaches us, but I think it's something we need to know."-John Gierach

http://fishingintheozarks.blogspot.com/

http://fishingintheozarks.blogspot.com/

Patroutbum on Apr 27, 2015April 27th, 2015, 10:52 pm EDT

I've always found that it's pretty easy to tell the difference, at least on the partially limestone stream the Yellow Breeches where I live. Stocked browns are heavily spotted and silvery. Wild browns have buttery yellow bellies, some have par marks, and all have crimson spots among other sparse spotting. Holdovers are a combination of those two depending on how long they've been in the stream. Holdovers had the same features as the wild browns but are typically larger and the features less distinct (pale orange spots). I have an entirely separate theory for brookies though.

"Trout are one of those creatures that are a hell of a lot prettier than they need to be. It gets you wondering about the inner workings of reality."

John Gierach

John Gierach

Quick Reply

Related Discussions

Topic

Replies

Last Reply

23

Aug 13, 2014

by Reelin_good

by Reelin_good

Re: East meets West: Todd's place on Cowden Lake, September 2020

In the Photography Board by Jmd123

+ 14

In the Photography Board by Jmd123

3

Mar 3, 2021

by Roguerat

by Roguerat

10

Feb 24, 2010

by CaseyP

by CaseyP