Hex Mayflies

Hexagenia limbata

The famous nocturnal Hex hatch of the Midwest (and a few other lucky locations) stirs to the surface mythically large brown trout that only touch streamers for the rest of the year.

Featured on the forum

This specimen resembled several others of around the same size and perhaps the same species, which were pretty common in my February sample from the upper Yakima. Unfortunately, I misplaced the specimen before I could get it under a microscope for a definitive ID.

Troutnut is a project started in 2003 by salmonid ecologist Jason "Troutnut" Neuswanger to help anglers and

fly tyers unabashedly embrace the entomological side of the sport. Learn more about Troutnut or

support the project for an enhanced experience here.

PaulRoberts on Aug 4, 2012August 4th, 2012, 6:47 am EDT

First, with all due respect, I would think Gary and Ernie would be happy to have their ideas discussed, even questioned. The result could be more evidence, such as the physiological mechanism employed coming to light.

That said, here are LaFontaine’s exact words:

“When a caddisfly pupa emerges it fills a transparent sheath around its body with air bubbles. These globules of air shimmer and sparkle as they reflect sunlight, creating a highly visible triggering characteristic. This sparkle is the key to imitating emergent caddisflies.

“…it initially cuts its way free of the cocoon and the insect drifts with the bottom currents, often for as much as fifteen or twenty feet, before generating the gas to fill the sheath around the body. ”

In this case, the light effect of the fly is the important factor. Trout quickly become super-selective to it, responding strongly to only that stimulus because it is so distinct.… The sparkle of a caddisfly pupa underwater is unmistakable.”

“… Many flies… make no attempt at all to simulate an air sack.”

“… In this living pupa, the skin is swelling at the thorax of the insect. If this emergent was still submerged, the greater pressure of the water would force this air back until bubbles completely surround the insect.”

The caddis pupa “gas sheath”/”air sack” is something I just haven’t been able to see on my own: on stream, in trout stomachs, or in Petri dishes. And I have not heard much from other anglers saying, “We saw it –the shimmering gas bubble!” Some of us, it would seem, would have seen this. The closest I have come has been with midge pupae from a trout’s stomach that floated in the dish. They were definitely buoyant as I could push them down and up they’d pop. But I saw no visible reflective bubbles.

Possibly, it only happens in natural circumstances, and as Gary describes, is of short duration. Maybe only SCUBA divers, with large numbers of emergents to watch, could see this. Gary Lafontaine and Ralph Cutter are the only ones I know of to have attempted this, and Ralph appears to agree with Gary even describing the gas bubble event in a natural pupa in that previous “Caddis Pupa Question” thread.

That said, here are LaFontaine’s exact words:

“When a caddisfly pupa emerges it fills a transparent sheath around its body with air bubbles. These globules of air shimmer and sparkle as they reflect sunlight, creating a highly visible triggering characteristic. This sparkle is the key to imitating emergent caddisflies.

“…it initially cuts its way free of the cocoon and the insect drifts with the bottom currents, often for as much as fifteen or twenty feet, before generating the gas to fill the sheath around the body. ”

In this case, the light effect of the fly is the important factor. Trout quickly become super-selective to it, responding strongly to only that stimulus because it is so distinct.… The sparkle of a caddisfly pupa underwater is unmistakable.”

“… Many flies… make no attempt at all to simulate an air sack.”

“… In this living pupa, the skin is swelling at the thorax of the insect. If this emergent was still submerged, the greater pressure of the water would force this air back until bubbles completely surround the insect.”

The caddis pupa “gas sheath”/”air sack” is something I just haven’t been able to see on my own: on stream, in trout stomachs, or in Petri dishes. And I have not heard much from other anglers saying, “We saw it –the shimmering gas bubble!” Some of us, it would seem, would have seen this. The closest I have come has been with midge pupae from a trout’s stomach that floated in the dish. They were definitely buoyant as I could push them down and up they’d pop. But I saw no visible reflective bubbles.

Possibly, it only happens in natural circumstances, and as Gary describes, is of short duration. Maybe only SCUBA divers, with large numbers of emergents to watch, could see this. Gary Lafontaine and Ralph Cutter are the only ones I know of to have attempted this, and Ralph appears to agree with Gary even describing the gas bubble event in a natural pupa in that previous “Caddis Pupa Question” thread.

PaulRoberts on Aug 4, 2012August 4th, 2012, 7:48 am EDT

OK...Since Ralph Cutter has been down there, what has he seen? Check this out (!); From Ralph Cutter's "Bugs of the Underworld" video series:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NGQEPZqNZU8

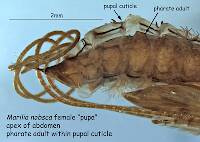

In particular see 1:00 into this 3min clip in midges. Pharate midges, apparently, can produce gas under the skin.

Cutter also states in his caddis section, and I’ve read this elsewhere, that lake dwelling caddis larvae, employing lightweight vegetation for their cases, can produce gas to buoy them up to the surface where wind current can redistribute them.

On pupae he says that many, but not all species, "glow like jewels".

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NGQEPZqNZU8

In particular see 1:00 into this 3min clip in midges. Pharate midges, apparently, can produce gas under the skin.

Cutter also states in his caddis section, and I’ve read this elsewhere, that lake dwelling caddis larvae, employing lightweight vegetation for their cases, can produce gas to buoy them up to the surface where wind current can redistribute them.

On pupae he says that many, but not all species, "glow like jewels".

GONZO on Aug 4, 2012August 4th, 2012, 8:22 am EDT

This is from an earlier post by Paul: Indeed. The following excerpt is from a 1979 paper by Stys and Soldan titled "Retention of Tracheal Gills in Adult Ephemeroptera and Other Insects." (Note: My emphasis is added in bold, and the word "air" is used, though perhaps just as a casual substitution for gas that includes O2): The full text of that paper can be found here: http://www.famu.org/mayfly/pubs/pub_s/pubstysp1980p409.pdf

This (how the pupa gets O2) is a pretty basic anatomical question that MUST have been looked into.

Respiration. The last larvae of Odonata, Plecoptera and Megaloptera always leave water prior to the larval/adult or larval/pupal ecdysis and at the same time they start breathing with an open (usually hemipneuistic) tracheal system. Moreover, a layer of air is eventually distributed below the apolysed larval cuticle and, consequently, there is no need for the already terrestrial pharate adults or pupae to use larval gills for respiration. Another situation obtains in the Trichoptera. There the pharate adult is fully aquatic and has to be considerably active while cutting its way out of the pupal case or cell and swimming to the surface where eclosion takes place. Although a layer of air is then already present between the pupal cuticle and the cuticle of the pharate adult which is already capable of breathing with open spiracles, it is possible that diffusion through the fine cuticle of pupal/pharate gills provides an additional and for some species necessary source of oxygen for the short period of intensive imaginal aquatic activity.

Falsifly on Aug 4, 2012August 4th, 2012, 8:44 am EDT

I’m certainly in no position to weigh in on the gas issue, but as it relates to the pharate diptera that I have observed, without the swimming motion they slowly descend. Whether aided by internal gas or not the swimming motion is what propels the ascent. My observations have shown what, for lack of a better term, contain periodic moments of rest, during which time the pupae sink. It’s equivalent to a two steps forward and one step back process.

As a side note, the surface tension is often referred to as a barrier which must be overcome, but I wonder that in some instances if it is what may provide the buoyancy needed for the final phase into adult?

As a side note, the surface tension is often referred to as a barrier which must be overcome, but I wonder that in some instances if it is what may provide the buoyancy needed for the final phase into adult?

Falsifly

When asked what I just caught that monster on I showed him. He put on his magnifiers and said, "I can't believe they can see that."

When asked what I just caught that monster on I showed him. He put on his magnifiers and said, "I can't believe they can see that."

PaulRoberts on Aug 4, 2012August 4th, 2012, 9:27 am EDT

the fine cuticle of pupal/pharate gills provides

Does this suggest that pharate caddis have gills?

GONZO on Aug 4, 2012August 4th, 2012, 9:55 am EDT

Does this suggest that pharate caddis have gills?

PaulRoberts on Aug 5, 2012August 5th, 2012, 5:58 am EDT

Thanks for that paper, Lloyd.

Shawnny3 on Aug 5, 2012August 5th, 2012, 11:15 am EDT

If the quibble is simply about the distinction between gas and air, I agree that there (obviously) is a difference. However, if it's obvious where an air-breather would get the air, I don't see why it is not just as obvious where a gas-breather would get the gas. :)

What I'm driving at is not that the type of gas used matters per se, but if an aquatic insect is forced to acquire or produce gas in a more complicated way than terrestrial insects do (which is likely), then the entire process of shedding the shuck may be different in aquatic insects in fundamental ways. Comparing the two may be apples and oranges.

And what self-respecting scientist says "air" when he means "unidentified gas"? Are entomologists really that sloppy? They don't strike me that way!

-Shawn

Jewelry-Quality Artistic Salmon Flies, by Shawn Davis

www.davisflydesigns.com

www.davisflydesigns.com

Entoman on Aug 5, 2012August 5th, 2012, 1:01 pm EDT

Wow, what a thread! I would have to be on the road for the last of it...:(

In relation to the gas vs. liquid question, perhaps gills and their function/activity isn't as significant a factor as we are assuming? I seem to remember a study done where baetid larvae had their gills removed and survived quite nicely. That aquatic insects absorb a good deal of oxygen through their cuticles has been well established, I think...

Gonzo - Thanks for pointing out the false quotations regarding LaFontaine. Rightly or wrongly, he has become the "poster boy" of the "bubble pupa" concept in angler discourse and it was in that vein (I believe in response to others having already done so) that I invoked his name - simply to facilitate the discussion. However, that's no excuse for contributing to another angler myth!:)

In relation to the gas vs. liquid question, perhaps gills and their function/activity isn't as significant a factor as we are assuming? I seem to remember a study done where baetid larvae had their gills removed and survived quite nicely. That aquatic insects absorb a good deal of oxygen through their cuticles has been well established, I think...

Gonzo - Thanks for pointing out the false quotations regarding LaFontaine. Rightly or wrongly, he has become the "poster boy" of the "bubble pupa" concept in angler discourse and it was in that vein (I believe in response to others having already done so) that I invoked his name - simply to facilitate the discussion. However, that's no excuse for contributing to another angler myth!:)

"It's not that I find fishing so important, it's just that I find all other endeavors of Man equally unimportant... And not nearly as much fun!" Robert Traver, Anatomy of a Fisherman

GONZO on Aug 5, 2012August 5th, 2012, 10:38 pm EDT

What I'm driving at is not that the type of gas used matters per se, but if an aquatic insect is forced to acquire or produce gas in a more complicated way than terrestrial insects do (which is likely), then the entire process of shedding the shuck may be different in aquatic insects in fundamental ways. Comparing the two may be apples and oranges.

And what self-respecting scientist says "air" when he means "unidentified gas"? Are entomologists really that sloppy? They don't strike me that way!

I'm not sure that respiration is necessarily "more complicated" in aquatic insects than in terrestrial insects, Shawn, but the use of the word "air" by scientists when it seemed unlikely that they were referring to "atmospheric air" did (and does) trouble me. And, as I mentioned before, I encountered this in more than one mention of the "gas" that fills the exuvial space in either general or specific reference to the molting process. However, one possible explanation might be suggested by two definitions of "air" that I found. (The first one is from the "Visual Thesaurus" and the second one is from the American Heritage Stedman's Medical Dictionary):

* a mixture of gases (especially oxygen) required for breathing

* Any of various respiratory gases. No longer in technical use.

Entoman on Aug 6, 2012August 6th, 2012, 4:07 pm EDT

Paul -

I have snorkeled quite a bit to check out what's going on down there, both to observe naturals as well as the behavior/appearance of imitations. For those of you that haven't tried it, water that looks amazingly clear looking down into it gets pretty cloudy when looking sideways through it, severely impacting the distance you hope to see clearly. Adding to this difficulty are the jumbled currents in the riffles where a lot of the caddis activity takes place. I must say it isn't easy to see much unless you're right next to it. These little critters are pretty small, and there is so much stuff in the drift! Also, your body affects currents such that drifting creatures are diverted away from you and a tremendous amount depends on the angle to catch the light right.

In spite of the difficulties, I have observed the flashy look of insects with entrapped air brought from the surface, but drifting nymphs and submerged pupae aren't in that group. That doesn't mean it isn't possible I suppose, only that I've never seen it. What I have seen is that Mayfly nymphs appear fairly opaque as well as caddis pupae for that matter, though the latter do take on a translucent glow or halo effect (for lack of a better description) when viewed from certain angles with the proper lighting effect and background. The darker species look black against the mirror with bright sky behind it, while the real pale ones tend to disappear. In any event, I wouldn't describe them as shiny or sparkly. In my view those are descriptions better reserved for flowing mylar strips that flash or gas bubbles that reflect like mirrors. BTW - flies tied with antron aren't shiny or sparkly underwater either, unless they contain a little trapped air.

Gary Lafontaine and Ralph Cutter are the only ones I know of to have attempted this Personally...

I have snorkeled quite a bit to check out what's going on down there, both to observe naturals as well as the behavior/appearance of imitations. For those of you that haven't tried it, water that looks amazingly clear looking down into it gets pretty cloudy when looking sideways through it, severely impacting the distance you hope to see clearly. Adding to this difficulty are the jumbled currents in the riffles where a lot of the caddis activity takes place. I must say it isn't easy to see much unless you're right next to it. These little critters are pretty small, and there is so much stuff in the drift! Also, your body affects currents such that drifting creatures are diverted away from you and a tremendous amount depends on the angle to catch the light right.

In spite of the difficulties, I have observed the flashy look of insects with entrapped air brought from the surface, but drifting nymphs and submerged pupae aren't in that group. That doesn't mean it isn't possible I suppose, only that I've never seen it. What I have seen is that Mayfly nymphs appear fairly opaque as well as caddis pupae for that matter, though the latter do take on a translucent glow or halo effect (for lack of a better description) when viewed from certain angles with the proper lighting effect and background. The darker species look black against the mirror with bright sky behind it, while the real pale ones tend to disappear. In any event, I wouldn't describe them as shiny or sparkly. In my view those are descriptions better reserved for flowing mylar strips that flash or gas bubbles that reflect like mirrors. BTW - flies tied with antron aren't shiny or sparkly underwater either, unless they contain a little trapped air.

"It's not that I find fishing so important, it's just that I find all other endeavors of Man equally unimportant... And not nearly as much fun!" Robert Traver, Anatomy of a Fisherman

Shawnny3 on Aug 6, 2012August 6th, 2012, 5:59 pm EDT

I'm not sure that respiration is necessarily "more complicated" in aquatic insects than in terrestrial insects

As I recall from intro biology (and keep in mind that this was 20 years ago and I was not a very good biology student), terrestrial insects don't really have a circulatory system for transporting dissolved oxygen, so they rely on diffusion of gases through pores in their bodies for respiration. This, as I recall, was used to explain a major reason insects cannot grow particularly large in an atmosphere of just 20% oxygen - diffusion is simply too inefficient to exchange gases fast enough. Is any of this correct, or have I somehow concocted some misconception in my mind?

-Shawn

Jewelry-Quality Artistic Salmon Flies, by Shawn Davis

www.davisflydesigns.com

www.davisflydesigns.com

GONZO on Aug 6, 2012August 6th, 2012, 6:53 pm EDT

Yeah, that sounds about right, Shawn. As I understand it, a few insects (like deepwater midges) do have hemoglobin, but the "blood" (hemolymph, an analog) and circulatory system in most insects is not used for carrying oxygen throughout the body. Methods of respiration can involve open or closed systems, continuous or discontinuous exchange, and are facilitated by everything from simple diffusion to various spiracles and/or gills. The Stys and Soldan paper that I linked earlier in this thread contains a lengthy discussion of this as it relates to both aquatic and terrestrial insects, but I've yet to find a reference that describes the precise process of gas exchange used when the molting fluid is replaced by gas (particularly in caddisflies, which are at issue here).

As for the concentration of atmospheric oxygen limiting ultimate size, apparently some Carboniferous and Permian insects had enormous wingspans, and I believe that atmospheric oxygen levels may have been much higher then. (One source mentions fossil Ephemeroptera with wingspans of 45 cm!)

As for the concentration of atmospheric oxygen limiting ultimate size, apparently some Carboniferous and Permian insects had enormous wingspans, and I believe that atmospheric oxygen levels may have been much higher then. (One source mentions fossil Ephemeroptera with wingspans of 45 cm!)

Jmd123 on Aug 7, 2012August 7th, 2012, 10:48 pm EDT

Gonzo, during the Carboniferous Era (including the Pennsylvanian and Mississippian Periods, if I'm not mistaken), it is believed that atmospheric oxygen levels reached 30-40%, much higher than today's approximately 21%. This was supposedly due to the enormous swamp forests that covered much of the land mass, then merged into one giant continent called Pangea (or Gondwanaland, forget exactly which). This has been shown through drilling into bubbles in amber, essentially fossilized tree resin that captured bubbles of the then existing atmosphere. During this period in Earth's history, evolutionary ancestors of today's modern dragonflies has wingspans of up to 30" from the fossil record!!! It is believed that the enormous size of these insects was due to the higher oxygen levels in the atmosphere (spiders also got to be the size of dinner plates - imagine that!). The insect respiratory system consists of simple tubes that penetrate the body and branch into smaller tubules, which allows only for diffusion of air into the body to major organs. Thus, our current maximum insect size of about 4" is restricted due to atmospheric oxygen levels.

Ever see the movie "The Mist", based on a Stephen King story? Sorry, those giant insects couldn't survive in our current atmosphere. And, if the oxygen did go up to 30-40% in our atmosphere? Well, don't light any matches, because forest fires were another whole story back in the Carboniferous Era...

Jonathon

Ever see the movie "The Mist", based on a Stephen King story? Sorry, those giant insects couldn't survive in our current atmosphere. And, if the oxygen did go up to 30-40% in our atmosphere? Well, don't light any matches, because forest fires were another whole story back in the Carboniferous Era...

Jonathon

No matter how big the one you just caught is, there's always a bigger one out there somewhere...

GONZO on Aug 8, 2012August 8th, 2012, 4:41 am EDT

Thanks, Jonathon. The idea of giant mayflies and dragonflies buzzing about reminds me of the D. H. Lawrence poem, "Humming-birds":

I doubt that Lawrence got the evolutionary details exactly right, but it is an appealing image.

A very minor point: I'm not sure about "allows only"(?). There's some distinction between passive diffusion and "ventilation" (muscular pumping of respiratory gases). In some insects (especially large or very active ones), I believe both are used.

I can imagine, in some otherworld

Primeval-dumb, far back

In that most awful stillness, that only gasped and hummed,

Humming-birds raced down the avenues.

Before anything had a soul,

While life was a heave of matter, half inanimate,

This little bit chipped off in brilliance

And went whizzing through the slow, vast, succulent stems.

I believe there were no flowers then,

In the world where humming-birds flashed ahead of creation.

I believe he pierced the slow vegetable veins with his long beak.

Probably he was big

As mosses, and little lizards, they say, were once big.

Probably he was a jabbing, terrifying monster.

We look at him through the wrong end of the long telescope of time,

Luckily for us.

A very minor point:

The insect respiratory system consists of simple tubes that penetrate the body and branch into smaller tubules, which allows only for diffusion of air into the body to major organs.

Sayfu

Posts: 560

Posts: 560

Sayfu on Aug 9, 2012August 9th, 2012, 9:47 am EDT

Shawnny. "I was not a very good student"..but you remember that from your biology class? Thanks a lot. I must be the village idiot.

Jmd123 on Aug 9, 2012August 9th, 2012, 7:33 pm EDT

Gonzo, I've seen a few wasps "pumping" their abdomens on occasion, usually on very hot days, but I don't think most insects have much means of forcing air into their tracheal system in anyway near the same way that creatures with internal, muscle-walled lungs have. At least, I didn't hear anything about it when I was taking my Insect Physiology class way back when...

Jonathon

Jonathon

No matter how big the one you just caught is, there's always a bigger one out there somewhere...

Shawnny3 on Aug 9, 2012August 9th, 2012, 7:51 pm EDT

Shawnny. "I was not a very good student"..but you remember that from your biology class? Thanks a lot. I must be the village idiot.

A fortunate bit of luck, I'm afraid. The problem with being a bad student is not that you don't remember anything, it's that you are never quite sure if what you remember you remember correctly. I'd make a terrible doctor: "I'm pretty sure that one is the spleen - let's take that out."

-Shawn

Jewelry-Quality Artistic Salmon Flies, by Shawn Davis

www.davisflydesigns.com

www.davisflydesigns.com

GONZO on Aug 9, 2012August 9th, 2012, 9:22 pm EDT

Gonzo, I've seen a few wasps "pumping" their abdomens on occasion, usually on very hot days, but I don't think most insects have much means of forcing air into their tracheal system in anyway near the same way that creatures with internal, muscle-walled lungs have.

Yeah, Jonathon, I think it's really a question of how many insects might use muscular ventilation (and the mechanisms involved), but it seems the view of that may be somewhat modified by recent research. Here's what The Insects--an Outline of Entomology by Gullan and Cranston (3rd edition, 2005) has to say about it:

Recently, rapid cycles of tracheal compression and expansion have been observed in some insects using X-ray videoing. Movements of the hemolymph and body could not explain these cycles, which appear to be a new mechanism of gas exchange in insects. In addition, large or dialated tracheae may serve as an oxygen reserve when spiracles are closed. In very active insects, especially large ones, active pumping movements of the thorax and/or abdomen ventilate (pump air through) the outer parts of the tracheal system and so the diffusion pathway to the tissues is reduced. Rhythmic thoracic movements and/or dorsi-ventral flattening or telescoping of the abdomen expels air, via the spiracles, from extensible or partially compressible tracheae or from air sacs. Co-ordinated opening and closing of the spiracles usually accompanies ventilatory movements and provides the basis for unidirectional air flow that occurs in the main tracheae of larger insects. Anterior spiracles open during inspiration and posterior ones open during expiration. The presence of air sacs, especially if large or extensive, facilitates ventilation by increasing the volume of tidal air that can be changed as a result of ventilatory movements.

Among other questions that this information raised for me, was whether the "push ups" that I have seen stonefly nymphs doing in the standing water of a collecting dish could be considered to be ventilatory movements or, as I have assumed, simply a way of moving the water so that the "stale" (exhausted) water around their gills could be refreshed. I suspect that it is probably the latter (true ventilation would seem to require an "open" system), but I'm not sure.

PaulRoberts on Aug 10, 2012August 10th, 2012, 5:13 am EDT

Looking at images of various caddis spp. pupa it appears some have notable external gill filaments, and others appear clear of them. I'm wondering if (some) caddis pharates have internal storage "air sacks".

Quick Reply

Related Discussions

Topic

Replies

Last Reply

40

Nov 23, 2015

by Martinlf

by Martinlf