September 7th, 2012

The temperature plummeted overnight, and I rose at 5:45 am to find a fresh dusting of snow all the way down to the road. I never take the time for elaborate breakfasts (such as hot oatmeal) on serious hunting and fishing trips, so I wolfed down a few handfuls of trail mix and set out up the mountain.

I had chosen the starting point for this hunt based on a movement pattern I noticed last year. I later realized there was no such pattern in action this year. It seems the most predictable attribute of caribou is their unpredictability, and this spot I had chosen might be no better or worse than any other access to high country in a hundred mile stretch of the highway. But it was harder to get into than most, as there were no good trails through a mile of snowy willow, alder, and dwarf birch thickets between the road and the easily traveled alpine tundra. The only trails in this mess were game trails, a confusing labyrinth of old caribou pathways that seemed to appear, disappear, split, or criss-cross every few yards.

In many places the brush rises six to ten feet high, and it conceals caribou (and even moose) easily, and it's no surprise I saw no wildlife as I picked my way through it. But once I hit the high tundra with a broad view of the brush below, I found a herd of caribou just a quarter mile downhill.

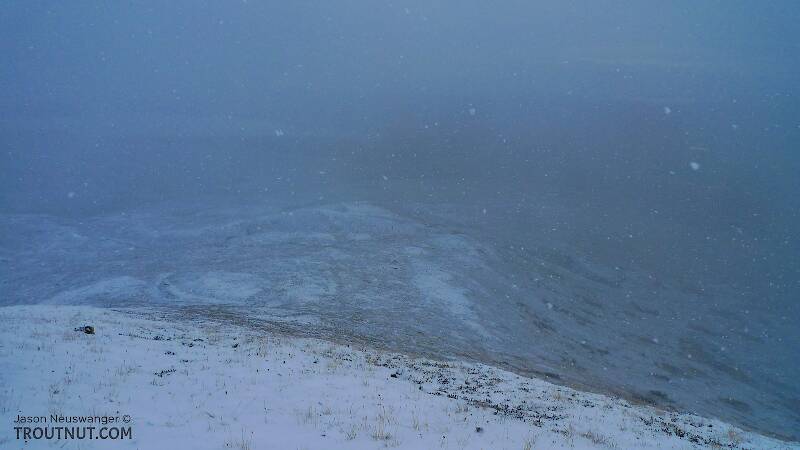

At first I saw only cows and calves, but by now I had figured out one of the cardinal rules of caribou hunting: even when the animals you see stick out like a blinking light, twice as many may be hidden by the brush and terrain right next to them. So I set up my spotting scope and watched for half an hour as ten caribou turned into twenty. They were still all cows and calves, so I kept moving up the mountain, and lost sight of the herd as a windless snow shower enveloped me.

The storm soon faded, and a great view of the next valley opened up from my position on a ridgetop at 4600 feet.

I briefly glimpsed more caribou descending a steep pass almost two miles away and a thousand feet above me. They dropped out of view before I could check for bulls, so I hurried toward a position where I thought I might intercept them. I only walked about 500 yards before they covered the two miles between us, so they appeared in my valley sooner than I expected, and not where I expected -- typical caribou. They came right over a steep ridge and crossed my tracks 225 yards behind me:

There were 10 of them, all cows and calves, so I didn't shoot, and noted the lesson that even the scent of my footprints could spook a herd.

After they left, the action slowed. I saw 3 more cows and calves in the distance as I wound my way up the ridge toward the next valley. Blue sky and sun were beginning to show, boosting the scenery from great to spectacular.

I finally reached a good viewpoint to scan the next valley, rimmed by massive peaks.

Despite my bird's-eye view of the snowy valley, it took several minutes to find the first caribou in plain sight 400 yards below me, the first bull of the day. He was grazing in the patch of green in the middle of the valley floor:

He was a smaller bull than I wanted to shoot so far from the road, so I did not stalk him. Instead, I sat and watched for half an hour, gradually amazed as another six cows and calves materialized on a piece of ground that seemed so obviously empty at first glance. Even knowing where they were, I could only find about half of them at any given time, because they blended in so well with the dark bumps of tundra vegetation peeking out of the thin blanket of snow. Eventually I was satisfied that I'd found all the caribou in this part of the valley, so I worked my way down the ridge, only to look back and find that the animals I was watching had grouped up, and there were fifteen of them, not seven. I had seen fewer than half. I set up the spotter to verify that there were no better bulls:

There was only the one small bull I saw earlier:

As I watched this group for a while from across the valley, caribou began to appear behind me, walking up into the valley along the side of my ridge. I twisted into a prone position with my backpack as a rest, and watched through my rifle scope as a herd of 25 cows and calves passed below me, followed by ten stragglers over the next half hour. A few of them saw me and got nervous, but they could not smell me, so they just stared for a while and continued on their way.

It was now early evening. Having seen so much action in this valley, I contemplated pitching camp in a sheltered notch on the ridgetop and waiting for something to happen toward dusk. But I have never been patient about letting my quarry come to me, so I decided to hike another mile to check out the next valley before dark. I knew I might be up high for a while, so I stopped at the bottom of this Valley of the Cows and Calves to refill my water from the pristine creek. I looked up from fussing with my filter to see a few cows and calves from a new herd appearing over the top of the ridge I was about to climb, 500 yards away.

I watched through binoculars as more and more bodies appeared on the skyline, and finally I saw some antlers that stood out from the cows. There were at least two bulls in this herd of about 40 caribou, and I liked the look of the biggest one. They were all so close together I could hardly make out one moving animal from another, but a glimpse of the bull was all I needed for now.

This herd quickly descended the ridge, letting me duck down low and use the terrain of the valley floor -- the bumpy moraine of a long-melted glacier, scattered with boulders and willows -- to close the distance. I gained maybe 30 yards while they walked closer to me, and I crouched behind knee-high, lichen-padded boulder that would make a perfect shooting rest. Now 250 yards away, the caribou were moving in and out of the cover on the valley floor, and I struggled to find the good bull in my scope. I finally found him, sparring lightly with the other bull, giving me brief peeks at their two racks clashing behind a tangle of willows. Both bulls moved out of sight.

Several long seconds later, I relocated my target as the herd started moving across the valley, angled away from me. I guessed how far they'd moved away since I ranged them, dialed my scope in for 280 yards, and hoped for a clear shot. Cows and calves kept crossing behind or in front of the bull, but finally he stood alone for a moment, broadside at 300 yards. I sent a shot from my .300 WSM. He dropped to the ground, but sprang back up and started limping away. He was hit in the lungs and one front shoulder, but I thought I might have only hit the leg, so I sent another shot that exploded the heart for an instant kill.

As soon as the adrenaline of the shot subsided, I was struck by the beauty of the place where I'd just taken my second caribou. The evening sun made the tundra glow in its fall colors, as the herd of caribou trotted away toward fog-draped, snow-capped mountains. I grabbed my camera in time to capture the herd moving on.

I wanted to remember the views as I approached the kill:

I was slightly surprised, but far from disappointed, to see that the size of the rack was average, not what most would consider a trophy caribou, and I had slightly over-judged it after looking at much smaller animals all day. But it was a personal best, with pretty symmetry and character, and the meat would be delicious. I knew I had taken the right animal at the right time.

It was 5:30 pm, and I had hours of work to do. I left the kill to set up a comfortable camp 300 yards away, then returned and butchered the carcass. I was not yet half done by dark, and I became a little bit nervous about standing over a reeking gutpile in the middle of the night with a weak headlamp, yelling every few minutes at imaginary bears to deter any real ones. By 2:00 am I had all the quarters and other meat cleaned, bagged, and cooling across the stream from the kill, and I collapsed in my tent for the night with a hot bag of Mountain House.