Salmonflies

Pteronarcys californica

The giant Salmonflies of the Western mountains are legendary for their proclivity to elicit consistent dry-fly action and ferocious strikes.

Featured on the forum

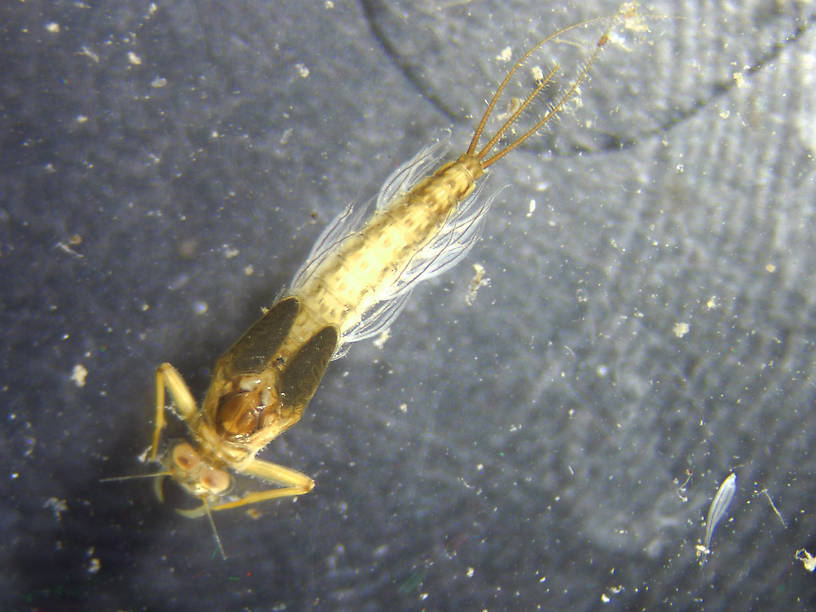

This is a striking caddis larva with an interesting color pattern on the head. Here are some characteristics I was able to see under the microscope, but could not easily expose for a picture:

- The prosternal horn is present.

- The mandible is clearly toothed, not formed into a uniform scraper blade.

- The seems to be only 2 major setae on the ventral edge of the hind femur.

- Chloride epithelia seem to be absent from the dorsal side of any abdominal segments.

Based on these characteristics and the ones more easily visible from the pictures, this seems to be Grammotaulius. The key's description of the case is spot-on: "Case cylindrical, made of longitudinally arranged sedge or similar leaves," as is the description of the markings on the head, "Dorsum of head light brownish yellow with numerous discrete, small, dark spots." The spot pattern on the head is a very good match to figure 19.312 of Merritt R.W., Cummins, K.W., and Berg, M.B. (2019). The species ID is based on Grammotaulius betteni being the only species of this genus known in Washington state.

- The prosternal horn is present.

- The mandible is clearly toothed, not formed into a uniform scraper blade.

- The seems to be only 2 major setae on the ventral edge of the hind femur.

- Chloride epithelia seem to be absent from the dorsal side of any abdominal segments.

Based on these characteristics and the ones more easily visible from the pictures, this seems to be Grammotaulius. The key's description of the case is spot-on: "Case cylindrical, made of longitudinally arranged sedge or similar leaves," as is the description of the markings on the head, "Dorsum of head light brownish yellow with numerous discrete, small, dark spots." The spot pattern on the head is a very good match to figure 19.312 of Merritt R.W., Cummins, K.W., and Berg, M.B. (2019). The species ID is based on Grammotaulius betteni being the only species of this genus known in Washington state.

Troutnut is a project started in 2003 by salmonid ecologist Jason "Troutnut" Neuswanger to help anglers and

fly tyers unabashedly embrace the entomological side of the sport. Learn more about Troutnut or

support the project for an enhanced experience here.

Mayfly Genus Paraleptophlebia (Blue Quills)

There are many species in this genus of mayflies, and some of them produce excellent hatches. Commonly known as Blue Quills or Mahogany Duns, they include some of the first mayflies to hatch in the Spring and some of the last to finish in the Fall.

In the East and Midwest, their small size (16 to 20, but mostly 18's) makes them difficult to match with old techniques. In the 1950s Ernest Schwiebert wrote in Matching the Hatch:

Fortunately, modern anglers with experience fishing hatches of tiny Baetis and Tricorythodes mayflies (and access to space-age tippet materials) are better prepared for eastern Paraleptophlebia. It's hard to make sense of so many species, but only one is very important and others can be considered in groups because they often hatch together:

In the East and Midwest, their small size (16 to 20, but mostly 18's) makes them difficult to match with old techniques. In the 1950s Ernest Schwiebert wrote in Matching the Hatch:

"The Paraleptophlebia hatches are the seasonal Waterloo of most anglers, for without fine tippets and tiny flies an empty basket is assured."

Fortunately, modern anglers with experience fishing hatches of tiny Baetis and Tricorythodes mayflies (and access to space-age tippet materials) are better prepared for eastern Paraleptophlebia. It's hard to make sense of so many species, but only one is very important and others can be considered in groups because they often hatch together:

- Paraleptophlebia adoptiva is by far the most important species of this genus in the two regions and is an early Spring emerger.

- Paraleptophlebia mollis, Paraleptophlebia guttata, and Paraleptophlebia strigula complement each other in late spring and early summer.

- Paraleptophlebia debilis and Paraleptophlebia praepedita occur together in the fall.

- The most important species is Paraleptophlebia debilis. This large (for the genus) Fall emerger can be found throughout the region. It is often accompanied by one of the slightly larger tusked species. Depending on locale, this can be Paraleptophlebia bicornuta (the most common), Paraleptophlebia packii or Paraleptophlebia helena. Check out their hatch pages for distribution information.

- Spring is the season for the smaller Paraleptophlebia heteronea throughout most of the region with Paraleptophlebia gregalis filling this niche in California and parts of Oregon.

Where & when

In 191 records from GBIF, adults of this genus have mostly been collected during July (27%), June (25%), August (16%), May (12%), September (9%), and October (5%).

In 54 records from GBIF, this genus has been collected at elevations ranging from 3 to 9751 ft, with an average (median) of 896 ft.

Genus Range

Hatching behavior

Though usually noted for migrating to the shallows to hatch, most species at times emerge in classic mayfly style on the surface and ride the water for a while before flying away. This is exacerbated by the inclement weather they often hatch in. Floating nymph patterns and emergers are very effective at these times. The hatch may last for a few hours each day.George Edmunds in Mayflies of North and Central America documented that Paraleptophlebia mayflies have been observed to emerge by crawling out onto shore when the water is high in the Spring, but since he gives no further details about which species do this it is reasonable to assume it's generic. Knopp and Cormier note in Mayflies: An Angler's Study of Trout Water Ephemeroptera the same behavior.

Spinner behavior

Time of day: Weather dependant

Habitat: Soft margins

Nymph biology

Current speed: Moderate to fast

Substrate: Sand, gravel, detritus

Specimens of the Mayfly Genus Paraleptophlebia

2 Male Duns

5 Female Duns

4 Male Spinners

5 Female Spinners

5 Nymphs

1 Streamside Picture of Paraleptophlebia Mayflies:

Discussions of Paraleptophlebia

Western Paraleptophlebia

17 replies

Posted by Entoman on Feb 4, 2012

Last reply on Feb 7, 2012 by Entoman

Paul wrote in another topic:

I largely agree, though they seem to be more tolerant of current than most genera of leptophlebiids. I have sampled them from riffles. In my experience (with an admitted western bias), they are far more important in the Fall. If an angler is lucky enough to be in place (and aware of them) when they are schooled up in preparation for hatching, some memorable nymphing can take place! :)

P. adoptiva is an eastern species. By far the most important species in the West is P. debilis, though they can be found mixed with others, particularly the unusual tusk bearing species bicornuta and in some locales packii. Anglers that occasionally come across these tuskers often confuse them with the immature burrowing ephemerids they resemble. Many anglers use their standard nymphs and do just fine with them. The PT is a popular pattern. Sometimes, a nymph that more accurately suggests their silhouette is the ticket. Because of their build and very obvious gills, they look more like a small long-tailed burrower than they do the typical baetid or ephemerellid, and it is good for the angler to keep this in mind.

Most duns and spinners are typically a rich brown, hence the name "Mahogany Dun." They can run the gamut from gray to almost black though, depending on the location. The slender bodies and coloration of the duns lead to them often being mistaken for baetids, but the oval vertically held hind wings and three tails make them easy to distinguish from that family. Check out this link to the hatch page for a look at the natural dun.

http://www.troutnut.com/hatch/752/Mayfly-Paraleptophlebia-debilis-Mahogany-Dun

Below are a couple of patterns I find very useful when this critter is about.

Mahogany Dun Nymph #16

Mahogany Paradun #16

Yes, the Paraleps can come about the same time as the tricaudatus, but don't start as early I think. And I think they were a mid-morning deal where tricaudatus has more of an afternoon peak. (Here in the rockies we're not supoosed to don't have the early P adoptiva, although last spring I found a single youngish nymph that my key would only take it to adoptiva -by gills if I remember right. Wish I'd pickled it and had it properly ID'd.

Anyway, back east I found the Paraleps emerged from slower currents and siltier substrates -often along stream edges. Whereas tricaudatus spilled out of the riffles. They could mix of course in certain places, but one could find one predominant if you wanted to (and I did bc I wanted to know each better), by focusing on key habitat.

Fly patterns could be identical really, although I had my own, esp for the nymphs. In fact, I'm still using some P adoptiva mimic parachutes (more a dun gray) during Baetis activity.

I largely agree, though they seem to be more tolerant of current than most genera of leptophlebiids. I have sampled them from riffles. In my experience (with an admitted western bias), they are far more important in the Fall. If an angler is lucky enough to be in place (and aware of them) when they are schooled up in preparation for hatching, some memorable nymphing can take place! :)

P. adoptiva is an eastern species. By far the most important species in the West is P. debilis, though they can be found mixed with others, particularly the unusual tusk bearing species bicornuta and in some locales packii. Anglers that occasionally come across these tuskers often confuse them with the immature burrowing ephemerids they resemble. Many anglers use their standard nymphs and do just fine with them. The PT is a popular pattern. Sometimes, a nymph that more accurately suggests their silhouette is the ticket. Because of their build and very obvious gills, they look more like a small long-tailed burrower than they do the typical baetid or ephemerellid, and it is good for the angler to keep this in mind.

Most duns and spinners are typically a rich brown, hence the name "Mahogany Dun." They can run the gamut from gray to almost black though, depending on the location. The slender bodies and coloration of the duns lead to them often being mistaken for baetids, but the oval vertically held hind wings and three tails make them easy to distinguish from that family. Check out this link to the hatch page for a look at the natural dun.

http://www.troutnut.com/hatch/752/Mayfly-Paraleptophlebia-debilis-Mahogany-Dun

Below are a couple of patterns I find very useful when this critter is about.

Mahogany Dun Nymph #16

Mahogany Paradun #16

Paralep Hatching Behavior

9 replies

Posted by Shawnny3 on Apr 6, 2009

Last reply on Apr 29, 2009 by Taxon

I can't remember where I read or heard these things (might have been on this site), but I want to make sure my vague recollections are not totally false. When Paraleptophlebia are mating, do they make exaggerated dives in clouds above the stream? If so, do they often end up in the water at these times or do they fall as spinners much later? Finally, when they emerge, do they do so at the stream bottom and then swim to the surface as duns?

Thanks for any help,

Shawn

Thanks for any help,

Shawn

Start a Discussion of Paraleptophlebia

References

- Arbona, Fred Jr. 1989. Mayflies, the Angler, and the Trout. Nick Lyons Books.

- Caucci, Al and Nastasi, Bob. 2004. Hatches II. The Lyons Press.

- Fauceglia, Ted. 2005. Mayflies . Stackpole Books.

- Knopp, Malcolm and Robert Cormier. 1997. Mayflies: An Angler's Study of Trout Water Ephemeroptera . The Lyons Press.

- Leonard, Justin W. and Fannie A. Leonard. 1962. Mayflies of Michigan Trout Streams. Cranbrook Institute of Science.

- Merritt R.W., Cummins, K.W., and Berg, M.B. 2019. An Introduction to the Aquatic Insects of North America (Fifth Edition). Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

- Schwiebert, Ernest G. 1955. Matching the Hatch. MacMillan Publishing Company.

- Swisher, Doug and Carl Richards. 2000. Selective Trout. The Lyons Press.

Mayfly Genus Paraleptophlebia (Blue Quills)

Taxonomy

Species in Paraleptophlebia

Paraleptophlebia associata

0

0

Paraleptophlebia bicornutaMahogany Duns

5

8

Paraleptophlebia brunneipennis

0

0

Paraleptophlebia californica

0

0

Paraleptophlebia clara

0

0

Paraleptophlebia debilisMahogany Duns

1

3

Paraleptophlebia falcula

0

0

Paraleptophlebia georgiana

0

0

Paraleptophlebia gregalisBlue Quills

0

0

Paraleptophlebia guttataBlue Quills

0

0

Paraleptophlebia helenaMahogany Duns

0

0

Paraleptophlebia moerens

0

0

Paraleptophlebia ontario

0

0

Paraleptophlebia packiiMahogany Duns

0

0

Paraleptophlebia praepeditaMahogany Duns

0

0

Paraleptophlebia rufivenosa

0

0

Paraleptophlebia sculleni

2

23

Paraleptophlebia strigulaBlue Quills

0

0

Paraleptophlebia vaciva

0

0

Paraleptophlebia volitans

0

0

Paraleptophlebia zayante

0

0

Species in Paraleptophlebia: Paraleptophlebia associata, Paraleptophlebia bicornuta, Paraleptophlebia brunneipennis, Paraleptophlebia californica, Paraleptophlebia clara, Paraleptophlebia debilis, Paraleptophlebia falcula, Paraleptophlebia georgiana, Paraleptophlebia gregalis, Paraleptophlebia guttata, Paraleptophlebia helena, Paraleptophlebia moerens, Paraleptophlebia ontario, Paraleptophlebia packii, Paraleptophlebia praepedita, Paraleptophlebia rufivenosa, Paraleptophlebia sculleni, Paraleptophlebia strigula, Paraleptophlebia vaciva, Paraleptophlebia volitans, Paraleptophlebia zayante

11 species (Paraleptophlebia altana, Paraleptophlebia aquilina, Paraleptophlebia cachea, Paraleptophlebia calcarica, Paraleptophlebia jeanae, Paraleptophlebia jenseni, Paraleptophlebia kirchneri, Paraleptophlebia placeri, Paraleptophlebia quisquilia, Paraleptophlebia sticta, and Paraleptophlebia traverae) aren't included.